“Most of us strongly believe that time spent in work is not where all the effort and outcome comes from,” he argues. “You should have time for keeping your health in check, your mental health in check…So we do strive for that balance.”

“Finns are pretty strict about 40 hours per week and we do have a lunch hour. It’s not like in the US where most people might just grab a sandwich on their way to the next meeting,” agrees Pauliina Alanen, a communications manager for an artificial intelligence company based at Maria 01, who previously worked in Silicon Valley. “And most people are off in July,” she adds. “Nothing happens here in July in [your] work life. Everybody’s in their summer cottage!”

Collaboration and communication

Scandinavia’s famous focus on collaboration and consensus-based decision making also plays a role in developing flexible working in Finland. Employers’ organisations, worker’s unions and politicians all helped to draft the new legislation, which was passed in parliament in March 2019 and is due for a final seal of approval by October.

As a result, there has been little major resistance to the idea, although some union representatives have expressed concerns about the shift towards remote working blurring the boundaries between work and private lives.

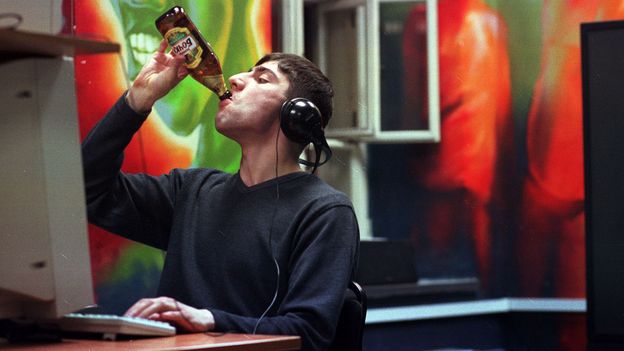

“There are risks. The employer can give too much work to the employee, who is afraid to say that there is no time to do it. The employee has very much to take care of herself or himself,” argues Anu-Tuija Lehto, a lawyer for the Central Organisation of Finnish Trade Unions, SAK.

She believes that even if workers and employers have written agreements, more fluid working hours may still make some staff feel like they need to “check e-mails and answer phones and be always available”, which could result in unpaid overtime.

Indeed, research into various flexible working arrangements around the world has suggested a tendency for people working irregular hours to put in more additional hours than those who work standard fixed hours.