Today marks the 30th anniversary of the plane crash that killed almost the entire Zambia men’s football team.

On 28 April 1993, travelling to Senegal for a World Cup qualifier, the squad’s plane stopped in Libreville in Gabon to refuel but came down off the coast not long after take-off.

According to the accident report, delayed by almost a decade, the right engine caught fire but the pilot shut down the still-functioning left engine and the aircraft plunged into the sea.

Eighteen players and 12 others on board lost their lives. No-one survived.

With a “golden generation” of young players tipped for great things, including World Cup qualification, the crash is viewed as one of the great disasters of African football.

But for Zambia, it also became the story of a remarkable revival as they quickly rebuilt their team. Poignantly, the Chipolopolo, a nickname that means Copper Bullets, would go on to become continental champions by winning the Africa Cup of Nations in Gabon 19 years later.

BBC Sport Africa has been speaking to the Danish coach who was given the unexpected job of bringing a shattered nation back together.

The common language of football

At the time of the crash, Roald Poulsen was a coach working in Denmark’s top tier.

With a strong pedigree, having already won both the Danish league title and cup, he was asked to take on the challenge of coaching an entirely new Zambia squad – one recruited at short notice that had never played together.

“Approximately three weeks after the disaster, I got calls from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Danish Football Association,” explained Poulsen, “[to ask] if I could help over a period of six weeks in Denmark.”

The plan was for the squad to spend three weeks in camp in Copenhagen followed by three weeks in the city of Velje. They would play games against teams at different levels of the Danish league system.

The party was made up of 16 players, two coaches and a physiotherapist.

“We were at the airport to welcome them but I had no clue about their football abilities.

“I didn’t know any of them. But the main thing is that the common language of football is so strong.”

After a conversation with the Zambian coaches, the initial focus was on fitness and the physical side of the game.

“I could see this was going to be a big job,” said Poulsen, whose early impressions were not favourable.

“I felt the ability of the players was not really there, that they didn’t have any confidence. All quite understandable given they were in foreign country with strange food and accommodation, far away from families.

“I didn’t know anything about them individually, not even what position they played.

“I set up training programmes and we trained twice every day. We had some days off, taking the players touring so they could recover a little bit.”

A captain’s return

Not every experienced Zambian international had been on board the doomed flight to Senegal.

Several players based in Europe had been due to make their own way to Dakar, including captain and PSV Eindhoven forward Kalusha Bwalya and Anderlecht midfielder Charles Musonda.

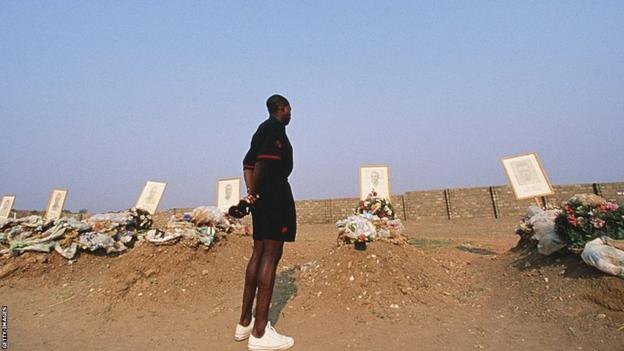

Bwalya still finds it hard to tell the story but he vividly remembers having a conversation with then Zambian president Frederick Chiluba after traveling home for the funerals.

It was Chiluba who insisted Zambia must look to rebuild, telling Bwalya he was needed as the figurehead for any new national team.

“Neither Kalusha or Musonda were in Denmark at that time,” continued Poulsen.

“I had no clue whether they wanted to join us. I suppose they had to stay with their clubs.”

But that changed after an edict from world football’s governing body.

“Fifa demanded the team go back to Zambia and play a World Cup qualifier against Morocco. That meant we were forced to cut short the camp.

“I was asked to go back with the team because the game against Morocco was within the six-week period and I was supposed to be in charge.

“Before we left Denmark, Kalusha Bwalya came with his family and watched one of the friendly games, and was ecstatic about what he had seen. The new players had made so much progress.

“He said it was his duty to be the captain and show them the way.”

‘A new national team was born’

The game against Morocco in Lusaka was Zambia’s first fixture in the second round of World Cup qualifying, with the original opener in Senegal having been postponed for obvious reasons.

“You can play as many friendly games in Denmark as you like but you never know whether you will be good enough going into a World Cup qualifier against one of the best teams in Africa,” said Poulsen, who was understandably nervous at finding himself cast in an unfamiliar role managing an Africa national team, especially with the focus of an entire country on him.

“The whole nation will be looking and wondering ‘Where have they been? What happened that they’ve been training in a Nordic country?’

“Every training session in the stadium was packed out.”

A third experienced player, Johnson Bwalya, joined Kalusha Bwalya and Musonda in the squad to bolster Poulsen’s new charges.

“It was a real manhood test because we didn’t know where we were in terms of playing at the international level.”

On 4 July 1993, the Chipolopolo players took to the field for a first competitive encounter since the crash that killed so many of their team-mates, colleagues and friends. Just 67 days had passed.

Poulsen was on the bench to watch his team come from behind to win 2-1.

“That was fantastic, mission accomplished. The whole nation accepted our work.”

Both Bwalya’s were on the scoresheet. Kalusha Bwalya, leading from the front as requested by his president, scored a spectacular free-kick that remains one of the most celebrated goals in the African game, symbolising recovery and healing.

“It took hours for us to leave the stadium as people ran alongside the bus, singing,” remembered the man who masterminded the victory.

“After less than six weeks, a new national team was born.”

So near and yet so far

In the end, Zambia missed out on qualification for the 1994 World Cup after a controversial loss in the return fixture against Morocco, who went on to win the group.

But just 12 months after the plane crash, they emerged as surprise finalists at the 1994 Africa Cup of Nations in Tunisia, pitted against Nigeria.

Pele, who was introduced to both teams pre-match, said his heart was “green”, a reference to Zambia’s playing colours.

But again, there was no fairytale ending as the Super Eagles triumphed 2-1.

Poulsen had not been involved in either near miss, having left at the end of his six-week deal as intended.

“Everyone wanted me to stay on but Zambia had made a deal with the English Football Association and that’s when Ian Porterfield took over.

“I was absolutely not surprised that the team did so well in 1994 Cup of Nations.”

But plenty of people did remember the contribution made by their new Danish father figure. When Porterfield left shortly after the final defeat to Nigeria, it was Poulsen who took over, spending two years in the job.

He would go on to coach in South Africa while also enjoying a second, shorter spell in the Zambia hot seat in 2002 – all opportunities he never considered until receiving that unexpected call in April 1993.

30 years on, as Zambia remembers the tragedy that struck its football team, it’s also worth remembering the man who helped rebuild it.