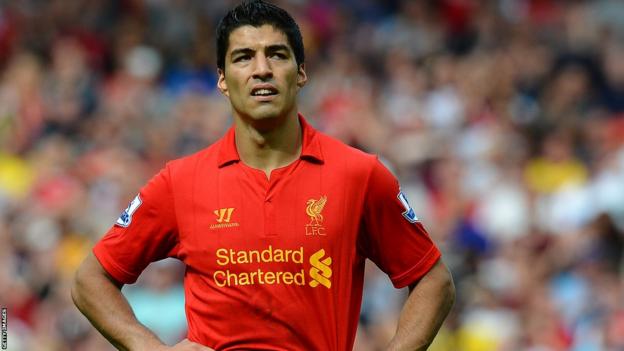

“Does Luis Suarez ring a bell?”

Dick Law has a wry chuckle as he introduces the Uruguayan into conversation.

Suarez isn’t being recalled for the scoring, bawling, biting or handballing. Instead, for once, it is something he didn’t do.

Ten years ago, in the summer of 2013, Law was in charge of overseeing Arsenal’s transfer business and manager Arsene Wenger wanted another striker.

At Liverpool, Suarez had scored 23 Premier League goals for a team that finished seventh and wanted to join another club.

So, Arsenal moved.

Having seen a copy of Suarez’s contract, Law knew it contained a clause mentioning bids over £40m.

Law also knew that figure was unlikely to be enough to buy Suarez – the clause was too vaguely written to force Liverpool’s hand. But he hoped that might be the number that started negotiations, fuelled Suarez’s desire to leave and paved the way to a deal.

Law sent over an offer of £40m, plus one symbolic pound.

“Our approach was just to start a conversation,” he says.

He didn’t get the reply he wanted.

“What do you think they’re smoking over there at Emirates?” tweeted Liverpool owner John W Henry in response.

An apparently unhappy Suarez skulked about in a couple of friendlies, but ultimately stayed at Liverpool, rather than submit a formal transfer request to up Arsenal’s ante.

“Was Suarez committed to leaving?” asks Law.

“If you are the buying club, you need more than a week or two. When things inevitably get sticky, you need a sense that the player is going to push from their end.

“In retrospect, should we have offered £45m? Sure. Would it ultimately have changed the outcome? I don’t think so.”

On that occasion Law lost out, but in the summer game of transfer bid and bluff, there is always another hand to play, another deal to do.

And strategy and tactics are critical if you are to win more than you lose.

The Charlie Chaplin. The Colombo. The Salami. Aim for the Stars. Tell Me Why. Sowing the Seed.

Dan Hughes’ tactical playbook runs to 39 different ploys and 12 pages.

A negotiation specialist, he was more used to talking it through with corporate business clients when, 15 years ago, he received a phone call.

Mike Rigg was on the line, trying to make sense of a world turned upside down.

Rigg had been appointed as Manchester City’s head of player acquisition just a few weeks before Sheikh Mansour had bought the club, suddenly swelling his transfer budget many times over and propelling him into competition with Europe’s superpowers.

Rigg had gained a fortune, but lost any leverage. As soon as City made enquiries, selling clubs ratcheted up the prices. Rigg couldn’t get a toehold in negotiations so he asked Hughes’ advice.

He was the first, but not the last.

Hughes and his firm Bridge Ability now advise a number of Premier League clubs, agents and even some players on how to get an upper hand in transfer negotiations. They also help deliver a Football Association course aimed at senior scouting staff and technical directors.

“Often these roles have been filled by ex-players or scouts,” explains Hughes.

“They are really good at the technical part of the job – spotting players – but when it comes to having to negotiate with a club or agent, they would end up having rings run around them.”

This is the advice of Law, Hughes and Damien Comolli, the former Liverpool and Tottenham director of football, now president at Ligue 1 Toulouse, on how to avoid being the boardroom fall guy at this time of year.

Know your enemy – and know yourselves

“My colleagues at other clubs were very capable and competent people, but each of them were working within the contexts they were given,” says Law.

“It was no good being [director of football] Txiki Begiristain at Manchester City and showing up in a deal and pleading poverty. But if you are [chairman] Tony Bloom at Brighton you can perhaps point to your balance sheet and say that you just don’t have the money.”

Being able to see the differing perspective and circumstances on both sides is key to predicting if a deal might be possible and, if so, at what price.

“That is the first fundamental thing,” adds Hughes. “An ability to step outside of your world and look at the other party’s pressures, problems and opportunities. Seeing the negotiation from their viewpoint changes everything.”

A shortage of players in a particular position, a windfall from a recent sale or an increasingly restless fanbase, might spur a buying club to pay more.

Conversely, similar options elsewhere on the market, a cautious owner, looming Financial Fair Play limits or emerging youth prospects may limit the chances of a bid being raised.

Either way, the idea of any player being worth a particular single amount is too simplistic.

What they are worth depends on who you are.

“At Toulouse, we are extremely data driven and every decision we make is analytics based,” explains Comolli.

“We make our own valuation – we don’t look at markets, we don’t look at websites or whatever.

“Sometimes we will pay more for a player, compared to how they are valued by the market generally, because we know what value they will bring for us specifically.”

Start the dance

You’ve identified a target. You’ve done your reconnaissance on their current club. The question is now how to start the dance.

As Law found out, pitch an offer too low and it can be used against you.

In the same summer as Arsenal’s failed attempt to sign Suarez, Everton described a £28m joint-bid from Manchester United for Marouane Fellaini and Leighton Baines as “derisory and insulting”.

Crystal Palace opted for “embarrassing” as their description of Arsenal’s £40m offer for Wilfried Zaha in 2019.

“Sometimes clubs genuinely feel they are being disrespected, sometimes it is a statement for the fans and the press,” says Comolli.

“We try to find the right balance between not upsetting people and not showing our hand too early at the same time. It is not easy and sometimes I make an offer way below what a club is looking for and they pull out.

“In that case I might use the player’s agent as a go-between to keep the dialogue going. It works most of the time – sometimes it doesn’t.”

Hughes believes clubs too often do the opposite though – paying over the odds for a player with an overly-generous opening offer.

“We encourage clubs to be bolder in general,” he says. “Sometimes things fall apart because you go too low, but far more common is for people to walk away from a negotiation thinking that the other party has accepted too easily.”

Law has been a beneficiary of such a misjudgement.

“In summer 2014, [former Arsenal chief executive] Ivan [Gazidis] and I walked into a room in Barcelona to meet Barcelona officials to talk about Alexis Sanchez. They said a price and it was cheaper than we expected to pay,” he recalls.

“Did we accept that price? Of course we didn’t, we tried to knock them down further!”

Sanchez, fresh from an impressive World Cup campaign with Chile, signed for £35m.

It isn’t just the substance of a bid that can cause offence, but the style of an approach.

Law was working for Arsenal, albeit in South America, in January 2005 when Ashley Cole, the club’s left-back, met with Jose Mourinho and Peter Kenyon, Chelsea’s manager and chief executive, in the Royal Park Hotel in central London. News of the gathering soon found its way into the press.

“What is important – regardless of how you acquire information or the conversations you may or may not have, or should or should not have – is to be respectful of the other club. That is critical,” Law adds.

“I think what was so striking about the Cole deal was simply the blatant, in-your-face nature of it.

“If you go to a hotel near Hyde Park, in the middle of London and you bring in your manager, who is a high-profile public figure… I just took it as a lack of respect for Arsenal, and if you don’t challenge that, what is next?”

Relations between the clubs deteriorated and Chelsea, Cole and Mourinho were all fined. But, 18 months on from the not-so-secret meeting, a deal was done to take Cole to Stamford Bridge.

There is theoretically another option.

Why not dispense with all plotting, low-balling and back-and-forth? Is it possible to enter negotiations with a first, best and final offer, a take-it-or-leave figure that cuts out the nonsense?

In theory, it should be. But transfer business is practised by humans, with quirks and expectations to be satisfied, in a long-established culture.

“The whole point of opening low is so that you move from it,” says Hughes. “It is the act of moving which gives the other side a sense of achievement – you want them to feel that they got the best deal they could.”

Find the power

One of the reasons a transfer deal can drag across a whole summer is the number of parties involved.

It may be presented as a simple transaction, but aligning different elements is key; get one wrong and even an apparently done deal can disintegrate.

“What we are talking about is three sets of negotiations: club to club, the player transaction and the agent transaction,” reveals Law.

“They are usually prioritised in that order, but sometimes they aren’t.

“Sometimes it is the agent you need to get right, sometimes it is a player conversation that you need to get right.”

Finding the “power behind the throne”, as Hughes describes it, can be a complex business. Kylian Mbappe’s inner circle has been subject to intense scrutiny as the France striker looks to force an exit from Paris St-Germain.

His agent and mother Fayza Lamari, his lawyer Delphine Verheyden, PSG’s Football Advisor Luis Campos and representatives Christophe Henrotay and Kia Joorabchian – who have previously been instrumental in deals involving Real Madrid – have all been cited as potentially key figures in unlocking a move to the Bernabeu.

Money is the fix-all grease for any cog in a deal, but occasionally less-wealthy clubs can find other trump cards to play.

Toulouse, promoted from the second tier in 2021-22, finished 13th in Ligue 1 last season, outperforming their budget – only the 18th-biggest in the division.

“We spend a vast amount of time talking to the player, his family, his partner, his parents to feel if he is a good culture fit for us,” says Comolli.

“We show them how we play and how, with the data, their playing style and abilities fit with ours. It is our due diligence, but the consequence is that the player feels charmed. It is a very strong convincing tool for any player.”

Law’s deals involved bigger names and numbers, but the process at Arsenal was similar.

“The first priority in a pitch to a player would be the realistic chances the club has to win a title – every good player wants to win a title,” he says.

“Then it comes down to the player’s assessment of the squad, particularly the people in his position.

“I also had the enormous advantage of having Arsene Wenger there. Players like stability, a carousel of coaches is a big issue for them.

“And location is important – the new stadium was a big plus and London was a big plus.

“I frequently told Brazilian players if they want to play in the rain, go to Manchester!”

Finding out which aspect of a move is important to a player can be straightforward. Other times, less so.

“It is a business about human beings,” says Law. “If you don’t like people or get on with them, it is a tough business. And if you can’t read between the lines it is very difficult to get good deals done.

“There are different dynamics to every deal. Take Granit Xhaka. I sat down with him over lunch and straight away you could tell he was a great guy, you just felt it.

“He was a serious, committed professional. He wasn’t joking around – we were there to have a serious lunch about the next phase of his career.

“Conversely I have sat down with players, who are so awkward socially it is hard to have any sort of conversation at all.”

Alternatives and illusions

In 1981, with the Cold War dangerously close to turning hot, Harvard professor Roger Fisher suggested implanting the United States’ nuclear codes within a volunteer.

It meant the country’s president, having to kill an unfortunate innocent to retrieve them, would only be able to press launch having confronted the consequences of doing so.

The same year, in a seminal negotiation book Getting to Yes, he came up with an idea that has lasted longer: Batna or the ‘best alternative to a negotiated agreement’.

“It is one of the things we always say – if you can walk away from a deal, it improves your power,” says Hughes.

“We try to be very disciplined,” adds Comolli of Toulouse’s approach to negotiations for targets.

“We have a ‘hard stop’ where we won’t go further. The upside of analytics is that you draw on a bigger pool than any scouting network. Our data covers 42,000 players. Sometimes we will have 20 targets for one position.

“If we are being priced out of a deal or the other club is difficult to deal with, we have no problem at all moving on to the next player on the list.

“When I came to Toulouse, I was absolutely desperate to go away from a situation where everyone at a club – the scouts, the manager – tell you it can only be that one player. That is the worst possible position to be in – you are being held to ransom, you have no leverage in the negotiation.

“I use the fact I have other options on a regular basis, and I am not bluffing, it is a reality. I don’t use it in a way of banging the table and slamming the door. I am very calm and realistic. I say, ‘if you don’t want to do the deal that is fine, no problem, I will move to the next one and we stay friends’.”

The selling club can do something similar, however. If negotiations hit a sticky point, news of rival interest – whether real or fictional – can add impetus to find a deal.

Liverpool – one of Comolli’s former clubs – have had three bids turned down by Southampton for midfielder Romeo Lavia this summer.

In the wake of Liverpool’s second unsuccessful approach, reports linking Lavia with Manchester United emerged.

At the same time though, Liverpool themselves were linked with a raft of other defensive midfield options, including Fluminense’s Andre, Crystal Palace’s Cheick Doucoure and Manchester City’s Kalvin Phillips.

“It is such a competitive industry, sometimes that is all they have to do,” says Hughes. “If you drop in the name of an arch-rival, values can suddenly go up, urgency can increase.

“Even if it is not done in the press, it can be dropped into conversation at a high level. Let’s face it, they all do it – clubs, agents, players, every party involved – if it suits their purpose.”

Establish a reputation

“Ain’t football changed?” remarked an incredulous Russell Brand on TalkSPORT last month.

“When I was a kid no-one knew stuff about chairmen and negotiators. I didn’t know about [former chairman] Terry Brown or whoever it is at West Ham.

“Why do I know that [Tottenham chairman] Daniel Levy is hard to negotiate with? It’s weird that we all know that kind of thing.”

Weird, but inevitable.

As scrutiny on transfer activity has increased over the past 20 years, how clubs – and the individuals that represent them – have acted in the past affects how others view them.

“In negotiation, perception is everything and everything you do leaves a legacy,” adds Hughes. “It is a huge thing for clubs to establish their reputation for how they do deals.”

For Law, there was a deal that, by breaking Arsenal’s transfer record by more than £27m after a period of relative frugality, marked a clear watershed.

“We signed Mesut Ozil in September 2013 and arguably, for that era, it was an expensive deal,” he says.

“It set a benchmark, a new parameter. Arsenal were willing to pay £45m-£50m for a player.”

From then on, other clubs came into negotiations with their expectations altered.

In the same way, Law had his own preconceptions about what doing business with a particular club or person would involve.

“If you do your homework, you know who you are dealing with,” he adds.

“Daniel Levy is one of the consummate negotiators in the business, I have the utmost respect for him.

“[Former chief executive] Marina Granovskaia at Chelsea – even though there was very much the sense of an open chequebook, I always sensed she drove a hard bargain.

“And when I dealt with [chief executive] Sergei Palkin at Shakhtar Donetsk over the sale of Eduardo, I found him a hard negotiator.”

The prospect of getting into negotiations with the most tenacious executives may be factored upon how clubs evaluate incoming bids and possible approaches of their own.

Act fast, think clear

Despite bringing in a record £105m via the sale of midfielder Declan Rice, West Ham, while closing in on Manchester United’s Harry Maguire and Southampton’s James Ward-Prowse, are still to finalise a major signing this summer.

Differences of opinion between manager David Moyes and director of football Tim Steidten are believed to be behind their slow business.

Both Law and Comolli agree that small, agile and aligned groups of decision-makers are vital in the race to secure talent.

“For me, the fewer number of people involved in the decision-making, the greater the chance of successful transfer business,” says Law.

“I think there is a tendency at a lot of clubs to get a lot of opinions in the room but, if you look at the most successful clubs, how many opinions are there that count?

“At Chelsea during Roman Abramovich’s ownership, how many were there that really mattered? At Man City, I get the impression it is just Begiristain, [chief executive] Ferran Soriano and Pep Guardiola. When Leicester City won the title, it was [director of football] Jon Rudkin, a couple more people and that was it.

“Not to throw a stone at Manchester United, but I always thought the problem there was too many cooks in the kitchen.”

“After getting a player hooked into the project, I would say the second most important thing is speed,” says Comolli.

“We have short decision-making chain. It is a strategy committee that consists of the head of data, head of strategy and culture, head of recruitment and myself.

“Once we decide to go it is a five-minute conversation or a text to the owners.”

For Comolli, there is an important caveat though. Selinay Gurgenc – the head of strategy and culture – has a duty to disagree. She has been tasked with challenging ‘groupthink’ – where small teams of decision-makers or Comolli himself blunder into irrational decisions – over transfers.

“When you are young, you are inclined to think you know everything, that you are the best thing since sliced bread,” adds Comolli. “You tend not to listen, but now I have made the conscious decision to surround myself with people who will ask, ‘what the hell am you doing?’.

“That helps a lot to keep calm, make the right decision and let the other clubs make the mistakes.”

We are entering the time when more mistakes are made.

The transfer window closes in England, Scotland and most of Europe on 1 September. As it approaches, the stakes rise and transfer business acquires a unique irrationality.

“In the rest of the business world, you might have Christmas or Easter – and there are hard deadlines around that – but most of the time if someone tries to draw a line in the sand and impose a deadline, it doesn’t actually matter,” explains Hughes.

“If a deal is actually finalised the week after, so what? Deadlines are often arbitrary.

“In football though, where it is set by a third party, it is absolute and very, very real. People will use it really effectively to suit their purpose, bringing a buying party right up to it by stalling.”

Bayern Munich seem set to live that truth.

They reportedly gave Tottenham a deadline of Friday, 4 August to accept a third and, they said, final £86m bid to sell them Harry Kane. The England captain himself is said to want any deal sorted before Tottenham’s first Premier League game against Brentford on Sunday.

Spurs chairman Levy ignored the first ultimatum and is unlikely to be bounced into a deal by the second.

Comolli worked with Levy for three years and says his ability to find the words and numbers to convince a player to extend their contract is unrivalled.

“Daniel Levy is the master at it, he is incredible,” adds Comolli. “He has mastered that science of approaching the player at the right time, with the right amount of money.

“I have grown up a lot though in keeping my distance from the madness or irrationality of the last few days of the transfer window. We try to avoid deals on deadline day.”

There will be plenty of clubs though who won’t.

They will be playing their hands late into the evening on 1 September, where the stakes are high, the bluffs are big and money, mistakes and reputations are made.