On 5 January 1971, Louis Herman Klotz did something that no basketballer has dared repeat.

In front of a disbelieving audience in the city of Martin, Tennessee, the man known as Red broke one of the most sacred unwritten rules in sport. As player-coach for the Washington Generals, Klotz shot the winning basket against the Harlem Globetrotters.

Everybody knows the Generals aren’t supposed to beat the Globetrotters.

“They looked at us like we’d just killed Santa,” Klotz would claim, as jeers rang around the university gymnasium.

Over more than 50 years since, the Globetrotters have been ruthless in meting out their revenge. To the unmistakable melody of Sweet Georgia Brown, they’ve showboated their way to victory at the expense of hapless Generals who’ve never again beaten their illustrious opponents.

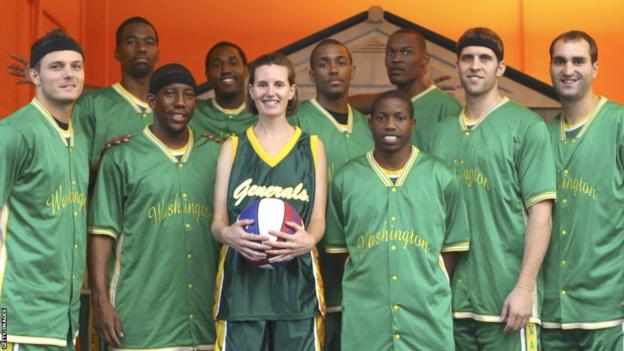

In contrast to the universal adulation enjoyed by the Globetrotters, those wearing the Generals’ infamously unsuccessful green jerseys are booed, ridiculed, and dunked on during defeat, after defeat, after defeat.

They are the rarest of sporting commodities: the underdogs you’re not supposed to root for. So why would anyone want to play for the Washington Generals?

“I had the time of my life playing with this team,” recalls Antoine Maddox, a Generals shooting guard between 2007 and 2010. “You’re travelling with one of the most famous teams in the world. That’s pretty awesome.”

Maddox’s first memory of the Washington Generals was on a career placement day at his high school in LaGrange, Georgia. Having told his teachers he wanted to be a basketballer, Maddox was given the opportunity to shadow ‘Sweet’ Lou Dunbar, the legendary Harlem Globetrotter. Before long, chasing Globetrotters shadows would be the eager schoolboy’s day job.

“I went to a game and I remember looking at the Washington Generals and thinking: ‘Man, I wonder how those guys got that job,'” Maddox says.

He’d find out soon enough when he was recruited at a post-college combine. The next NBA stars are often discovered at these open trials, though many players attend with more modest hopes of a professional career overseas. Those left behind are prime targets for Generals scouts.

“I still had some aspirations of going to play pro somewhere,” says Maddox, who now works for a Californian tech company. “I figured at least I would be travelling and maybe there’d be some opportunity to get seen in front of some other teams.”

The Globetrotters live up to their name, playing hundreds of games a season during a comprehensive Stateside tour followed by whistle-stop trips to Europe, South America and Asia. And wherever they go, their rivals follow.

“It was the best experience you can ever have coming right out of college. I ended up hitting 26 different countries in my three years,” says Maddox.

Occasionally there are visits to US military bases. David Birch, who spent five years with the Generals, remembers high-security trips to Japan, Germany, Lebanon, and even Afghanistan.

“In Afghanistan, if you stepped outside of your base, you had to have a helmet and vest on,” he says. “It was strict but very rewarding because you got to see overseas troops and provide them with entertainment. They were always very appreciative.”

While Birch admits that nobody is getting rich from a rookie contract with the Generals, playing basketball on an all-expenses paid world tour isn’t a bad way to cover the rent back home.

“I thought it was a great deal,” he says. “I’m getting paid to come out, shoot some threes, and travel.”

Caleb Kimbrough’s fond memories of a season with the Generals include a game on the rooftop of the former home of the Philadelphia 76ers, and playing to a sold-out Madison Square Garden. He’s proud to have played a small part in Globetrotters folklore.

“I really appreciated being a part of basketball history,” he says.

Founded in 1926, the Harlem Globetrotters actually originated in Chicago. At a time when basketball remained segregated, owner Abe Saperstein – white, Jewish and born in London – added the Harlem handle to indicate to audiences that his team were black.

The Harlem Globetrotters would go on to inspire a generation of black Americans by regularly beating the country’s top all-white basketball teams. In 1950, Globetrotters Chuck Cooper, Nat Clifton, and Hank DeZonie were among the first black players to feature in the NBA.

Having helped to break the sport’s racial barriers, Saperstein’s outfit no longer needed to beat the NBA elite to prove a point. Instead, they grew their mainstream appeal by ramping up the theatrics.

Saperstein wanted his Globetrotters to travel with a trusted foil capable of giving his guys a contest every night.

He decided to call a flame-haired point guard who, at 5ft 7in, remains the shortest-ever NBA champion following a 1948 win with the Baltimore Bullets. He was Red Klotz.

The World War Two veteran agreed to put together a crack squad of ballers and named his new franchise in honour of General Eisenhower.

Despite the symbolism of the name – that of a stuffy elite set to be humbled by anti-establishment mavericks – it was likely unintentional on Klotz’s part.

He preferred to describe his team as the Ginger Rogers to the Globetrotters’ Fred Astaire, and in 1952, the Washington Generals began their decades-long dance with their Harlem foes.

But, by the time their founder shot that controversial winner as a sprightly 50-year-old in 1971, any notion of the Generals being considered exceptional players in their own right had long diminished.

Even the occasional rebrand, to aliases including New Jersey Reds and New York Nationals, failed to prevent them from becoming a pop culture synonym for luckless losers.

And it continues to this day.

You might have seen Harvey Specter cruelly quipping about the Generals in the TV series Suits, or the episode of How I Met Your Mother where Ted and Marshall scream at a biased ref while wearing green jerseys. And then there’s The Simpsons, where Krusty the Clown curses a losing bet on the team with the line: “I thought they were due!”

In each case, the viewer doesn’t need the joke explained. The Washington Generals have become a punchline.

Being the butt of the joke extends on to the court, too. From throwing buckets of water to pulling down shorts, many of the antics are straight from the circus. But if the ringmasters are in blue, it’s those in green playing the sad clown.

“I’d have my jersey torn off in the middle of the game, and I had to run off the court in my boxers,” says Kimbrough, laughing. “And I did the balloon free throw,” he adds, referring to a skit where the basketball is replaced with a helium-filled flyaway.

But not everyone is comfortable acting the fool. When you’re accustomed to being the college headliner, playing second fiddle can take some getting used to. Throw in a gruelling travel schedule and player turnover is high.

“It could be frustrating at times, as you would imagine,” admits Kimbrough. “It was a revolving door. There was the main part of the roster that stayed, those guys just got it. But there were others who’d get frustrated at the disparity. They don’t treat you equally, but you know that going in.”

Birch says: “You’d see people cut mid-tour. For tons of reasons. I’ve seen people quit mid-game.”

He recalls one occasion when a team-mate resigned over lunch.

“They want to make sure the Globetrotters eat first so they can go do autographs,” he says. “So even though we would be in the cafeteria first, we would have to wait. And that would get under some people’s skin.”

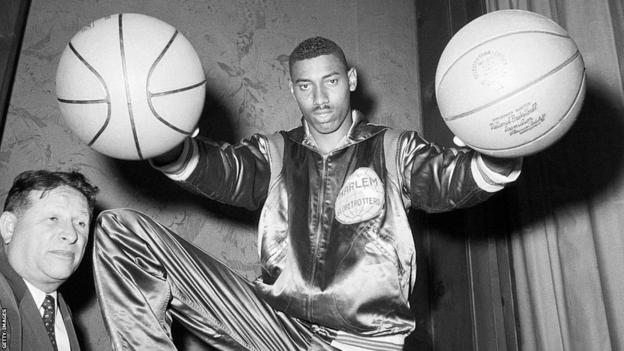

There was a time when a basketballer could earn more as a Globetrotter than as a pro. In 1958, college star Wilt ‘the Stilt’ Chamberlain toured with Saperstein’s travelling crew until he was old enough for the NBA.

He would soon become the league’s highest-paid player when he signed a $30,000 rookie contract with the Philadelphia Warriors (around £250,000 today). Yet for Chamberlain, that represented a pay cut. He’d earned double that for a year on the road in the red and white shorts.

Other legends, such as Meadowlark Lemon and the aforementioned Dunbar, were also household names in their day. While today’s line-up may not enjoy the same renown or recompense, spin-off TV shows and appearances in everything from Sesame Street to Ninja Warrior mean there’s a good chance even fairweather basketball fans can name a Harlem Globetrotter. Current showman Thunder Law has multiple Guinness World records and 64,000 social media followers.

Naming a Washington General is a trickier task. None are currently listed on the Globetrotters website, nor were any named in the programme on the latest UK tour. Any contrarians hoping to buy Generals merchandise at a show will also be disappointed.

Fans with a Magic Pass can shoot hoops with the Globetrotters two hours before tip-off. During the game, the stars are mic’d up to engage directly with the audience. They also stay on the court for a “fifth quarter” signing session.

In contrast, the Generals appear when they’re booed on and then slink off, defeated, at the buzzer. The only time they’re handed a mic is to call the place a dump.

“You’re not allowed to stay on the court and get pictures. You’re not allowed to do autographs. You’re not allowed to do any press,” says Birch.

“There’s not a whole lot of fan interaction for us. It’s more just, we’re there, we play our game, and then we head off the court,” says Maddox, noting that it can prove a tough baptism.

“In the beginning, that’s kind of an ego check. Because maybe you want to be part of that stuff.”

Some tours can offer a remedy. In parts of the world where the Globetrotters narrative isn’t as familiar, the Generals enjoy rare moments of recognition.

“There were people in China and South America, places where basketball is not really the main sport, where they had no idea it wasn’t the NBA,” remembers Birch.

“They would treat us like they would treat the Globetrotters, wanting our pictures and our autographs.

“We thought it was cool. It was the only time we would play somewhere where you got to feel what it was like to be a real NBA professional.”

Despite the disparity in pay, workload, and acclaim, the relationship between Generals and Globetrotters is warm. Especially overseas, when the two squads travel in close quarters.

They also share a secret.

“Nobody signed up thinking they were winning,” admits Birch, addressing the elephant in the room.

“If you’re somebody who wants to play real basketball, and you’re too competitive, then it probably isn’t for you. Because you’re just going to get frustrated and be one of those people that quits.”

Just how much of a Globetrotters show involves genuine, competitive, five-on-five action? It’s the question you’re not supposed to ask.

The organisation is understandably coy on the matter and active players aren’t permitted to discuss in-game mechanics. And who can blame them? There’s a reason Mickey Mouse never removes his head at Disneyland.

“They would always talk about how they don’t want to ruin the magic of the show,” says Birch, before providing insight that would have got him sacked before he left in 2015 to become a teacher.

Birch describes rehearsing scripted show plays at pre-season camp, but also notes that games included segments termed a “play one”. These were unscripted moments that allowed for genuine guard-and-block competition.

“When I started my first year, almost half the game was play one. We knew how the fourth quarter was going to go, and we knew how the first quarter was going to go. But the second and third you just played it out,” says Birch, who, as on-court coach, was responsible for ensuring his team-mates stuck to the formula.

“By my fifth and final year, it had graduated from a kind of pick-up game with a comedy aspect, to a full-on kid show. So we only had three or four play ones the entire game.

“I came in as a basketball player, and I left as an actor.”

Former players like Birch may be free of omertas, but just as you don’t expect Steve Austin or The Rock to reveal professional wrestling’s secrets in retirement, most Generals veterans continue to play along.

“We had a lot of close games. We had some opportunities. But yeah, we came up short,” says Maddox, unable to hide a grin.

“We had some nail-biters. But never won,” says Kimbrough, with an exaggerated shake of the head.

But for tenacious competitors who’ve grown up dreaming of the NBA, standing idly as the Globetrotters unleash another dizzying weave must jar with their innate sporting urges.

“It was difficult,” acknowledges Kimbrough, who is now a college basketball coach in Virginia. “But there were portions of the game where you’re just playing. We would play hard, and your competitive juices start to flow. And there were times where we did really well.”

Sometimes, a little too well. Kimbrough recalls a game at the home of the Chicago Bulls when the Generals were warned during the interval.

“We made so many threes that we were ahead significantly. And I remember we got a stern talking-to from one of the coaches.

“Obviously, the Globetrotters miraculously came back and won the game. But all of us Generals felt, ‘Oh yeah, we won that one.'”

But any player threatening to overshadow the Globetrotters will not spend long on court.

“There might be a situation where I’ve made five or six three-pointers and the Globetrotters can’t make any shots, where their coach will be like, ‘take him out’. They don’t want us looking better,” says Birch.

While a tactical analysis of a Globetrotters game is a fool’s errand, watching the Generals in isolation from their free-wheeling adversaries makes for revealing viewing.

With the dazzling dunks reserved for their opposition, the Generals are restricted to efforts from distance. Without the privilege of dunking the rebound when they miss.

Yet they rarely do, regularly landing consecutive three-pointers and even the occasional four-pointer – a Globetrotter innovation that rewards accuracy from even further back.

Make no mistake, the Generals can shoot. There’s no faking that.

“You can’t take away from making a half-court hook shot,” says Kimbrough, who has encouraged several of his top students to join the Generals.

While Globetrotters are often recruited for having an extraordinary trait – the short guard who can jump high, the towering centre who doesn’t need to, the speedy forward with turbo handling – the Generals epitomise function over flair.

“They’re more of your tried-and-true traditional basketball type of player,” explains Maddox. “You have to be a good utility player. Very good with the ball, a good passer, very knowledgeable about the game.

“Your average person on the street might look at a game and think, ‘I can take a Washington General.’ But, you know, they probably can’t,” adds Maddox, who still attends Globetrotters games every year, decked in green and cheering for his old team.

Birch, a Hall of Fame scoring leader when at Ottawa University, is also keen to point out that his team-mates were no mugs.

“If you play for the Generals, you still have to be a high-level college player. We had a lot of players who scored more than 2,000 college points. There are guys that can really play.”

So if the sides were to play each other in a strictly competitive fixture, without scripts, props or phoney officials, would they fancy their chances?

“If you asked any General, they would tell you 100%,” insists Birch. “They’d say the Generals are the more well-rounded players that can actually play real basketball, and if we played for real, we would win more than they would.

“Globetrotters would tell you: ‘No, we have the tricks, but we’re also more skilled too.'”

So given that the Generals are, despite their reputation, talented and highly driven athletes, is there the slightest temptation to register a victory for the first time since 1971?

It’s the question fans would ask Birch more than any other. But he insists that in order for that to happen, everyone including the referee, timekeeper, and announcer would have to be in on the ruse.

And as fun as it might sound, few on the payroll are willing to jeopardise their livelihoods for the sake of a little notoriety.

“We would get people that would ask: ‘Hey, why don’t you just go win one time?’ But your contract will be void because you didn’t do your part in the show. And this is our job. A lot of people wouldn’t risk that.”

It’s why that infamous win in Tennessee likely occurred from a combination of timekeeper error, rare wasteful shooting from the Globetrotters, and a legendary General who could get away with it.

After all, Red Klotz’s franchise may have lost more than 17,000 games, but he maintained until the day he died in 2014 that his team always tried to win.

Will it ever happen again? You never know. The Generals are due…