At Chad Jones’ feet is a sports bag that contains six boxes, each valued at between about $10,000 and $30,000 a pop.

This inconspicuous holdall, which a few minutes ago was slung over his shoulder on its journey from the boot of his car to our table, is easily worth over six figures.

The commodities Jones sells are not antiques or diamonds; they’re not fragile or laden with weight. They’re not handmade and they’re not particularly robust, either. They are highly collectable, artistically created and of an aesthetic born in his hometown of New York City. We’re talking trainers – or sneakers as they say in the United States. And yes, they really are that valuable.

Jones, a 41-year-old former college basketball player from Brooklyn, also known as Sneaker Galactus, specialises in collecting and selling unique footwear – those of limited production runs or symbolic of rare sporting backstories.

He keeps them all in pristine, boxed condition – a prerequisite for any self-regarding sneakerhead – and on racks he picked up from a closing Foot Locker store. It’s a lifelong passion that has evolved into his livelihood, a business he has grown from a side hustle in his school days.

“When I was in college, my mother lost her job,” Jones explains. “I had a car and my mother was paying for it. She told me she could no longer pay, so I started flipping [my extra pairs] out of the trunk.

“I’d buy a pair of Air Jordan Concord 11s for $150 and sell them for $350. I sold enough to be able to get me through college and pay for the car. So I always knew there was something there.”

It’s no coincidence that Jones was so drawn to these shoes, having grown up in 1980s Brooklyn. After all, it was this area of the five boroughs that benefited from some of the most important drivers of the sneaker culture we know today: hip hop, street basketball and Michael Jordan.

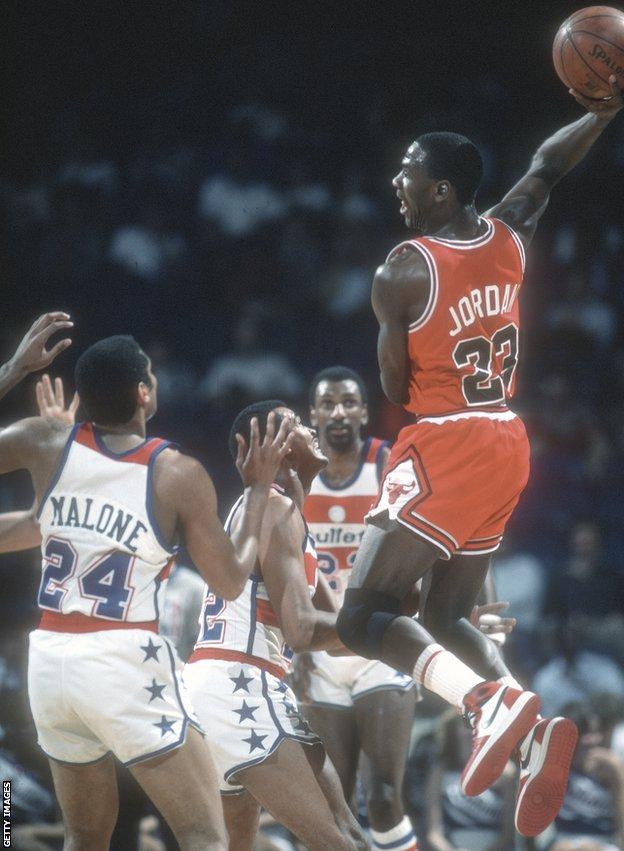

Arguably the greatest player to ever shoot hoop, Jordan was born in Fort Greene, Brooklyn, just a few miles from Jones’ childhood home, although he moved to North Carolina at a young age.

Jordan’s status in the eyes of 1980s USA was already rarefied thanks to his prowess on the court with the Chicago Bulls, but when almost exactly 35 years ago, on 15 September 1985, Nike released the Air Jordan 1s, it gave the fan on the street a tangible way to bring a little of his prestige to their own person.

For many, the Air Jordan 1s are the shoe that kickstarted the global sneaker resale market, an industry recently valued at $6bn (£4.6bn) by Cowen Equity Research and predicted to be worth $30bn (£23bn) by 2030. It is a theory seemingly supported by the eye-watering figures this particular model of trainer has sold for at auctions in 2020 during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Boosted by the release of the popular Last Dance Netflix series, which documents Jordan’s exploits at the height of his aerial powers, both Sotheby’s and Christie’s have registered record prices at recent auctions.

A pair of game-worn Air Jordan 1s High, replete with an embedded shard of glass from a backboard shattered by a particularly powerful Jordan dunk, sold for a record $615,000 (£468,000) at Christies this August. That merely followed the previous high watermark set by a Sotheby’s auction held in May, when another signed pair of Air Jordan 1s netted $560,000 £426,000).

The Air Jordan 1s are of particular value. They were they designed by legendary sneaker designer Peter Moore. They reflected Jordan’s specific request to feel ‘closer to the court’ by removing the air bubble from the sole. And they were also famously banned by the NBA within a month of release.

This led to a notoriety among fans that quickly turned the sneaker into a sales phenomenon. Nike, ever attuned to a marketing opportunity, exploited the situation with a widely broadcast advert that boasted: “Fortunately, the NBA can’t stop you from wearing them.”

Demand was so high that Jordan sneaker muggings and attacks became commonplace in many American cities. A killing over the trainer promoted Sports Illustrated to run with a cover story title: “Your Sneakers or Your Life.”

Jones himself experienced the violent side associated with demand for sneakers when in 2012 – at a New York release of the Nike Kobe 7 models – he was stabbed while camping overnight outside the store in a queue. It’s an incident he chooses to no longer revisit in interviews.

The Air Jordan 1s’ release was a seminal moment according to Simon ‘Woody’ Wood, founder of global trainer magazine Sneaker Freaker, and not just because of the cultural hype.

“One of the beautiful things about the shoe is the quality of the leather,” he says. “I have a pair of Jordans here from 1985. The leather is thick as anything. It feels like they just sliced a chunk of cow off and stitched it to the shoe. They’re pretty much indestructible.”

Woody, based in the Australian city of Melbourne, is something of an expert on the subject. Having started the Sneaker Freaker magazine as a cult read and vehicle to get free sneakers from manufacturers in 2002, Woody’s business has since ballooned into a website, a merch business, a creative agency and a magazine that’s now sold in 40 countries. Most recently he authored a 700-page book called The Ultimate Sneaker; to which nearly forty pages were devoted to Jordans alone.

“I mean really I could’ve filled the entire book on Jordans,” he says. “In terms of investment that might’ve been a smarter move right now! It’s the only brand really based on an athlete. And, he’s the Supreme Being, a god around which a whole mystique has been built.

“The Americans love him as a winner, a guy who comes from nowhere and becomes the most famous and wealthy person ever. But physically to watch him jump from, you know, beyond the three point line and sink a basket, he was just so good. And the shoes really locked into that aspect of him.”

The brightness of the star factor associated with the Air Jordan 1s has been key in helping them remain, in a galaxy of standout sneakers, the most coveted for those with money to spend. Especially for “cashed up guys in their 40s and 50s” who remember Jordan at his height, Woody believes.

Another secret behind the mystique, he suggests, lies in the enduring appeal of their design features. There’s the ‘wings logo’ – inspired by airline badges of the time – the red, white and black colours that echoed Jordan’s Chicago Bulls affinity, and ‘classic panelling’ that help to build the sneaker’s ‘story’. A story that was given a new chapter in April this year when Dior teamed up with Nike to release a new, co-branded version of the model that retailed for $2,000 (£1,520) a pair.

Featured on the cover of Sneaker Freaker, the shoe quickly sold out when a staggering five million people tried to buy the 8,500 pairs released. Online marketplace StockX shows the shoe drawing anything up to $20,000 on its real time price graphs that one would associate more readily with trading stocks.

Covid-related economic volatility, it seems, is not a problem in the sneaker resale niche, where profits are not only increasing but markets are expanding.

For Jones, his day to day may now be in Fort Lee, New Jersey – where his white-soled sneakers benefit from sidewalks that are “thankfully cleaner than in New York” – but his future profits will increasingly be drawn globally.

Local knowledge used to be key in sourcing sneaker gems, as boutique stores and little-known outlets across New York City would sell their limited supplies to in-the-know hunters. Though he still refers to his hometown as the “world Mecca for sneakers”, the bulk of Jones’ purchases are made online via a network of other collectors, with sales increasing in hotspots like Asia. It has helped him amass over 1,100 pairs in total, and some of his favourites are in the black sports bag on the floor below.

“This is a PlayStation Air Force 1 anniversary shoe, only 50 pairs in the world. Made in 2009 by Nike and worth around $10,000,” he says, matter of factly. “These are Stash Zoom Kobe 1s, made in collaboration with NORT in 2006, They’re worth about $20,000.”

Designs associated with players like the tragic figure of Kobe Bryant help to drive prices higher, but ultimately it’s the discerning eye of the collector that sets the value: beauty being firmly in the eye of the buyer.

It was an appreciation Jones’ wife, Adena, struggled to come to terms with when the couple first started dating. Admitting to suffering vertigo from sleeping under the great walls of boxed shoes that lined his apartment, she came to understand their value when her then boyfriend linked his Paypal account to hers. It allowed him to showcase the sale returns of his accumulating assets in real time.

“I quickly realised their power. I saw $8,000 come in from two pairs and I was like: you’re right, this is it! I tell people part of our home is paid for by sneakers. This ring, my wedding ring, is paid for by sneakers,” she says, proudly holding forth her sparkling rock.

As co-founder of Another Lane, a new online business run in partnership with Jones that targets aficionados priced out by the recent sneaker boom, Adena is now convinced of what her husband has known since childhood: sneakers are more than just shoes, they are prized symbols of identity. In fact, Jones goes as far to suggest they have political symbolism too.

“Sneakers were originally white because that was the colour of the tennis-playing elites,” he says.

“People who look like me traditionally served those people, that’s why wearing the colour white is so significant in the black community. Wearing clean, white sneakers means you can afford them and you’ve elevated yourself in society.”

It’s a sentiment echoed by Elizabeth Semmelhack, senior curator of Toronto’s Bata Shoe Museum and author of Out Of The Box: The Rise Of Sneaker Culture.

“Having enough money to step out in a ‘fresh’, pristine and unscuffed, pair of Nikes became a point of pride, a symbol of rugged individualism whose fashion was hyper-masculine and easily marketed in ways that capitalised on both its American-ness and its exoticism simultaneously,” Semmelhack says.

“Can sneakers be used in a political way? 100% yes. It’s why stepping on someone’s prize pair can be deeply offensive.”

Semmelhack sees a through line from the nouveau riche, tennis-court origins of the mid-19th Century sneaker to rapper Jay-Z’s affirmation that he would only ever wear a pair of white trainers once to maintain his crisp aesthetic. It’s a notion Jones intrinsically understands.

“It’s like, yo, that kid, he always got a fresh pair of sneakers on, I wonder what he does? It’s like there’s this mysteriousness, a question mark: what is this guy really about?” he says.

Thirty-five years on, it seems hang time footwear has lost none of its potency.