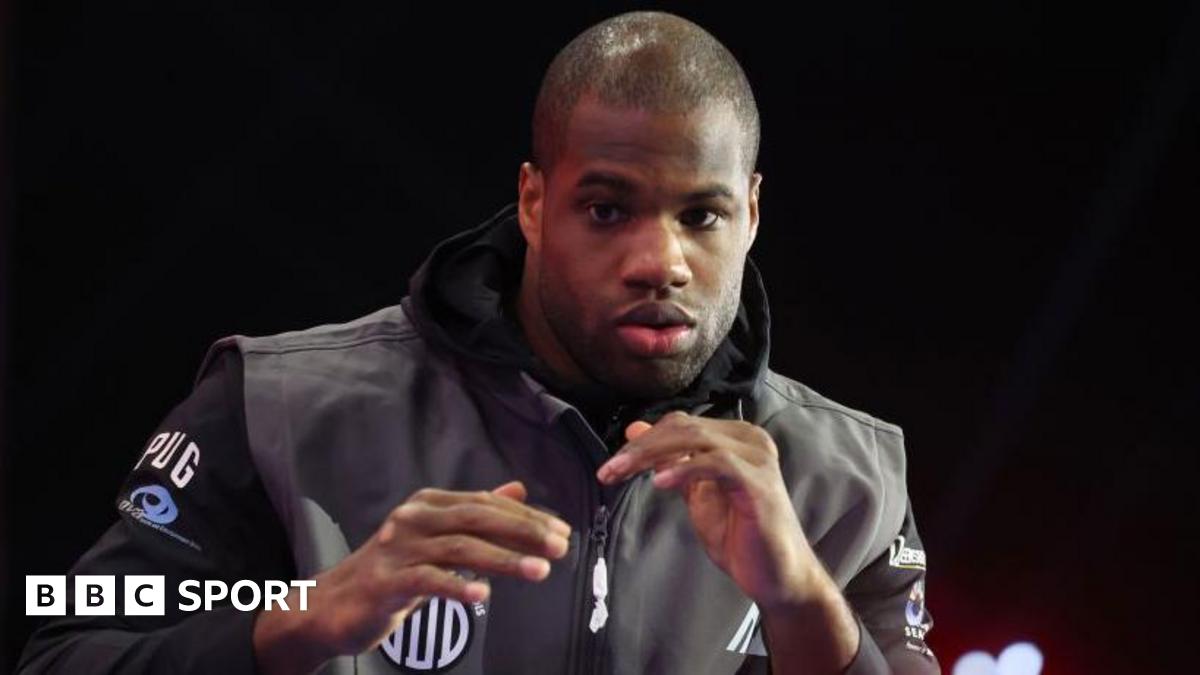

Andy Murray cried. Dan Evans cried. Even BBC television presenter Clare Balding cried.

In the moments after Murray’s illustrious career came to an end at the Paris 2024 Olympics, there was an outpouring of emotion.

It was felt at Roland Garros by Murray, by his British team-mates, by the thousands of adoring fans chanting his name.

It was also felt across a nation which will never see one of its sporting icons play professionally again – and Balding’s reaction probably summed up the feelings of many who have watched this British hero over the years.

“Obviously, it was emotional because it’s the last time I will play a competitive match,” said Murray, who was also applauded by his mother Judy watching on.

“But I am genuinely happy just now. I’m happy with how it finished.”

Murray is no stranger to getting emotional in public, of course.

Most famously, there were the tears on Wimbledon’s Centre Court after losing to Roger Federer in the 2012 final, finally endearing him to a larger share of the British public.

“This isn’t going to be easy…” he said to Sue Barker on court post-match that day, before the tears came.

Before that, he welled up after losing the 2010 Australian Open final to Roger Federer – quipping he could “cry like Roger… it’s a shame I can’t play like him”.

Once he did land that Grand Slam title – and two more after that – it was injury that led to more tears.

In 2018, he sobbed uncontrollably under his towel at the Washington Open as he battled through hip pain.

On the eve of the 2019 Australian Open, Murray broke down in a pre-tournament news conference when he revealed he might have to retire because of impending hip resurfacing surgery, which he thought would end his career.

Five and a half years later, and after squeezing every last drop out of his comeback, Murray was finally content to call it a day.

“It’s been really hard. Physically, pain-wise, I feel bad,” he said.

“Physically, I can obviously go on the court and perform at a level that’s competitive.

“We were close to getting in the medal rounds here. That’s OK but the pain and discomfort in my body is not good and that’s also why I’m happy to be finishing.

“If I kept going and kept trying, eventually you end up having an injury potentially ending your career.

“I know that now is the right time and physically.”

After the initial tears at Roland Garros had dried, a contemplative Murray revealed how tough the final few months had been for him.

An ankle injury in March disrupted what was already planned to be his final season and when he did manage to race back, his participation in an emotional goodbye to Wimbledon came under threat as he needed back surgery to remove a cyst.

Murray had long conceded he was unlikely to have a “perfect ending” but admitted he “fast-tracked his rehab” in order to play at the Olympics.

“I’m glad I got to go out here and finish on my terms,” he said.

“At times in the last few years, that wasn’t a certainty.

“And even when I first went to have my scan on my back, the issue that I had with it, I was told that I wouldn’t be playing at the Olympics and I wouldn’t be playing at Wimbledon.

“So I feel lucky I got that opportunity to play here and have some great matches and create amazing memories.”

Murray means a lot of different things to a lot of people who don’t even know him: Sporting icon who has taken British tennis to new heights; advocate for gender equality in a male-dominated sport; all-round decent guy with acerbically dry humour.

The droll side of his personality came out again shortly after he had finished speaking to the media.

“Never even liked tennis anyway,” he wrote on social media. The bio on his X account had also been changed from ‘I play tennis’ to ‘I played tennis’.

Some loved him. Some never got him but were eventually won round. Some have never got him at all.

“He’s a class act and has been for years for British tennis and world tennis,” said Evans.

“He has spoken up on matters other people wouldn’t speak about. He’s a good guy.”