Sign up for notifications to the latest Insight features via the BBC Sport app and find the most recent in the series.

“Mr Galliani, can I take the Champions League trophy to Ukraine?”

Adriano Galliani’s face lit up. Milan, the club he helmed as vice-chairman to Silvio Berlusconi, had just won Europe’s premier club competition for the sixth time, defeating Juventus on penalties at Old Trafford in the 2003 final.

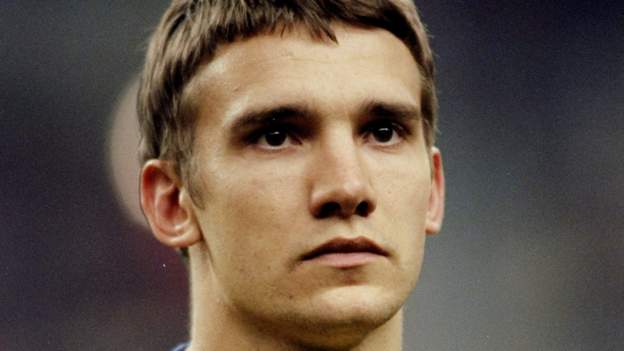

Now, here was the striker who had taken the winning spot-kick in his office with an unusual request.

“Come with me, Sheva. Quick!”

The older man marched him down a short corridor to the trophy room of one of the giants of European football.

“Andriy, choose the one you want. There are six of them!”

Andriy Shevchenko pointed to the last in line, the one he had lifted into the Manchester night a few days earlier. Shortly afterwards, that trophy was beside Shevchenko on a private plane bound for Kyiv.

The reason? As he remembers in his new autobiography, My Life, My Football: “Promises must be kept.”

Shevchenko had made his promise the moment the final whistle blew to end a one-of-a-kind semi-final: Internazionale v Milan, both legs played at their shared San Siro home.

He made it to the man he credits with laying the foundations for all his success: the Champions League, Serie A, the 2004 Ballon d’Or, leading Ukraine into their first World Cup as an independent nation. A man who had died a year earlier.

If I get my hands on that trophy, I will bring it to you, Valeriy Vasilevic.

As a sign of his respect, Shevchenko always addressed his former coach by his ancestral patronymic name, but football history remembers him as Valeriy Lobanovskyi, a revolutionary sporting mind whose success spanned three decades in three spells as manager of Dynamo Kyiv in the home city he shared with Shevchenko.

Lobanovskyi was at once a ruthless physical trainer and an ingenious tactician, an early adopter of computer analysis and a master psychologist. His great teams – generations apart – shared common elements that run through some of the best sides of the 21st Century: the ability to press opponents deep in their own territory; systems that allow footballers to rotate positions; the constant drive to create numerical supremacy in key areas of the pitch.

He is without question one of the founding fathers of modern football. However, as Shevchenko reflected on his journey home with the Champions League trophy by his side, had a few key moments in a handful of games during a 30-year career gone differently, Lobanovskyi might be remembered as the greatest coach of them all.

Having played as a midfielder for Dynamo and the USSR, Lobanovskyi returned to take charge of his former club in 1973, after an impressive apprenticeship at Dnipro. During this first stint, he developed the ideas and systems which would underpin his entire career. He was the frontman in a four-strong coaching team. Former team-mate Oleh Bazylevych led training, while Anatoliy Zelentsov, a scientist from the Dnipropetrovsk Institute of Physical Science, managed the physical preparation of the players, and statistician Mykhailo Oshemkov collated and analysed the data that drove the operation.

Lobanovskyi’s first great team won the 1975 European Cup Winners’ Cup, defeating Ferencvaros 3-0.

That autumn they added the European Super Cup, beating European champions Bayern Munich 1-0 in Germany and, in front of 100,000 supporters, 2-0 in Kyiv.

Oleh Blokhin scored all three goals and ended the year with the Ballon d’Or.

Blokhin was the sole survivor from that team when Lobanovskyi returned from a short stint in charge of the Soviet Union to guide Dynamo to their second Cup Winners’ Cup in 1986. Blokhin scored the signature goal in a 3-0 win over Atletico Madrid, at the end of a beautiful, sweeping attack that methodically moved the defenders out of position like chess pieces. This time he was partnered in attack by Ihor Belanov, who became the second of Lobanovskyi’s players to win the Ballon d’Or when he pipped Gary Lineker to the prize that year.

To get to the motivation for Shevchenko’s flight to Kyiv in 2003, however, we need to look beyond the silverware and instead at the near misses suffered by Lobanovskyi’s teams in Europe’s premier tournament.

In 1977, two years after their triumph in the European Super Cup, Dynamo again faced Bayern. They were paired in the European Cup quarter-finals, with a star-studded Bayern team – featuring several of West Germany’s world champions, including Franz Beckenbauer and Uli Hoeness – attempting to lift the trophy for a fourth successive season.

After losing 1-0 in Germany, Dynamo scored twice in the final 10 minutes of the second leg to end Bayern’s supremacy. However, in the semi-finals their fortunes were reversed as Dynamo defeated Borussia Monchengladbach 1-0 in Kyiv before going out to a late goal in the second leg in Germany.

In 1987 Dynamo once more reached Europe’s final four, but were defeated 2-1 in both legs by Porto, who would win the trophy for the first time that year.

Lobanovskyi twice led his team to the European Cup quarter-finals in the intervening years, but fell both times to the eventual winners – Aston Villa in 1981 and Hamburg in 1982.

Shevchenko and Lobanovskyi first met in 1997, when Lobanovskyi returned from a six-year spell in international football, coaching the United Arab Emirates and then Kuwait. It was Lobanovskyi’s third and final spell at Dynamo, but his legacy at the club was already enshrined.

“As a sign of thanks and recognition, the club had always kept his office at the stadium. When he came back, he was coming home,” recalled Shevchenko.

“He was a genius. A visionary. A subversive, perpetually on the trail of perfection.”

In each of their three seasons together, Dynamo, Lobanovskyi and Shevchenko would win the domestic double of league and cup. In Europe much had changed, in both sport and politics, but, once again, Lobanovskyi’s team made their mark there too.

Ukraine had achieved independence in 1991 and Dynamo were no longer at the top of a powerful Soviet system of player development and sports science.

Instead, they were a comparatively provincial contender in a competition of super-clubs who could fill their rosters with the most expensive players from all over the world. For Dynamo, the pathway to the latter stages was also far more treacherous since a shift away from a straight knockout format.

In 1997-98, to make the quarter-finals they would have to navigate two rounds of qualifiers and a group system in which they were seeded fourth.

Lobanovskyi remained wedded to the ethos upon which he had built all his success: team over individual. “Everybody must fulfil the coach’s demands first, then perform his individual mastery.”

Before a ball was kicked in the 1997-98 Champions League, the coach’s demands were made clear at a gruelling training camp in Germany that showed Dynamo’s players that the legends surrounding the returning Lobanovskyi’s methods were true.

“I witnessed experienced players crying at his feet, begging him to call off the session early. He always refused,” said Shevchenko. “In my own timeline he is ground zero. There is the time before Lobanovskyi and the time after.”

As Shevchenko neared recovery from a knee injury in time for the 1997-98 Champions League, Lobanovskyi had one more test for him to pass. “I had to run the 300m to the stadium five times, with three minutes of rest between each run. The last one felt like the Green Mile, the last walk undertaken by those on death row.”

The methods may have been extreme, but the results were spectacular.

Dynamo had been drawn with PSV Eindhoven, Newcastle United and Barcelona in a brutal group. Each of Lobanovskyi’s great teams had operated with two versatile forwards, capable of playing deeper roles and of moving into wide areas, to create space for advancing midfielders. This time those roles would be played by Shevchenko and Serhiy Rebrov.

Both scored in a 3-1 win in Eindhoven and again when Dynamo hosted Newcastle in a 2-2 draw. In the first match of a double-header against Barcelona, Dynamo won 3-0, with Rebrov among the scorers.

In Spain, 21-year-old Shevchenko announced himself to the world, scoring a first-half hat-trick as Lobanovskyi’s team dismantled a Barcelona side led by Louis van Gaal and featuring Luis Figo and Rivaldo. Rebrov added his fourth goal in four games to seal a 4-0 win.

Dynamo’s players danced in front of a small section of away support, the blue and yellow flags of their country fluttering in the fast-emptying stands.

Afterwards, Lobanovskyi took Shevchenko aside. “This is just the beginning,” he said. “You’re reaching a level that only a few ever attain. Don’t stop. Don’t ever be satisfied.”

After topping the group, Dynamo fell to eventual finalists Juventus. But in the following season’s tournament, they were even better.

Dynamo trumped Arsenal, Lens and Panathinaikos to finish top of their group once more and set up a two-legged quarter-final against Real Madrid.

Real, with a line-up decorated by Roberto Carlos, Clarence Seedorf and Raul, were defending champions and heavy favourites.

The first leg, in Spain, was drawn 1-1. Then, in front of 81,500 of their own fans, Dynamo won the return 2-0. Having scored Dynamo’s only goal of the first leg, Shevchenko scored both in the second, put in on goal by brilliant Rebrov throughballs on each occasion on a freezing Kyiv night.

The victory secured Dynamo a third Champions League semi-final under Lobanovskyi, 22 years after the first.

By this time, Shevchenko and Lobanovskyi shared a secret unknown to anyone else inside the dressing room: it would be their final European campaign together.

A deal had already been done with AC Milan and Shevchenko would leave for Italy at the end of the season in a £20m move.

In the semi-finals, Lobanovskyi faced old adversaries Bayern.

In Kyiv his team led 3-1 with 12 minutes left to play as Shevchenko scored his seventh and eighth goals of the tournament that season. They had chances to add to their lead, but late goals from Stefan Effenberg and Carsten Jancker drew Bayern level. In Germany a single Mario Basler goal meant Bayern, and not Dynamo, who would face treble-chasing Manchester United in the final.

“I hated seeing the expression on Lobanovskyi’s face,” said Shevchenko of that night in Munich. “I could see how much he had wanted to win that trophy.”

Less than three years later, on 13 May 2002, Lobanovskyi collapsed on the touchline during Dynamo’s match against Metalurg Zaporizhzhia and never recovered. Shevchenko got the news while on a post-season tour of the United States with Milan and flew back to join almost 200,000 people mourning a sporting icon on the streets of Kyiv.

Dynamo’s stadium, which would be renamed in Lobanovskyi’s honour later that year, became a temporary funeral home and Shevchenko lined up to pay his respects.

“I was thinking irrational thoughts,” Shevchenko said. “I kept thinking he would get up from this eternal sleep, send away the doctor who had misdiagnosed him, there in front of everyone, just as he had a medic who once tried to have me miss training because of a fever.”

In spring 2003 a statue of Lobanovskyi was erected outside the stadium which bears his name. There the great coach, rendered larger than life and in bronze, perches on the end of a bench, in constant observation – a giant, watching over the city and its footballers.

And it is there that Shevchenko was bound, just a few months after the statue’s unveiling, with the one piece of silverware that had eluded Lobanovskyi. He slipped the European Cup on to the bench, next to his old coach, and stepped away, so he could see the two of them together at last.

“From that moment on, the memory of him in 1999 became a little bit sweeter,” said Shevchenko. “He smiled more, I smiled more. There has always been a part of him inside me. He was a European champion now too.”