This weekend is all about the king. Saul ‘Canelo’ Alvarez, the main man of Mexican boxing, returns to the city where it all began.

Undisputed super-middleweight champion Alvarez defends his IBF, WBA, WBC and WBO titles against Briton John Ryder at Guadalajara’s Estadio Akron on Saturday.

‘The King is coming home’ is the strapline for the bout as fight fever hits the historic city in the state of Jalisco, home to tequila and mariachi music, harder than a trademark Alvarez body shot.

“It’s an honour. I’m happy to be part of this history in my own town,” 32-year-old Alvarez, who will fight Mexico for the first time since 2011, says.

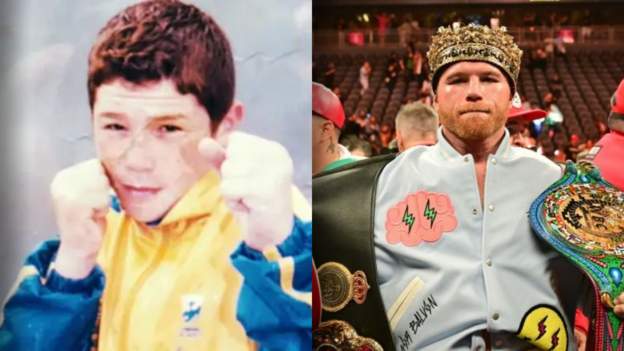

The teenager bullied for his red hair and freckles has grown to become world boxing’s hottest property. He has gone from selling ice creams on a bus to selling out stadiums. The Alvarez story is as inspiring as it is remarkable.

A quiet kid sparring world champions

Boxing has a long history of rags-to-riches success stories. Manny Pacquiao, the eight-division champion from the Philippines, escaped a life of hardship on the streets of Manila, selling bread and later working as a janitor to make ends meet.

Mike Tyson resorted to theft from the age of 10 to survive the dangers of Brownsville, Brooklyn. He went on to become the youngest heavyweight champion of all time.

The Alvarez tale could sit easily alongside those two.

“Canelo comes from a very small suburb of Guadalajara,” boxing broadcaster and analyst Claudia Trejos says. “His dad owned an ice cream parlour. He would get off school and go sell ice creams.”

Alvarez had ambitions. Inspired by his older siblings who all boxed, at 13 he found haven in father-son duo Jose ‘Chepo’ and Eddy Reynoso’s gym.

Journalist Kiko Baldares, who has worked for Team Canelo, recalls their first meeting.

“He was a very polite, quiet and nice kid,” he says. “Even at that age, he was so focused on boxing. He wanted to learn everything he could from the older fighters.”

The 15-year-old pro who became a teenage dad

Alvarez turned professional two years later, aged 15. Outside of the ring, however, his life took an unexpected twist the following year when his then-girlfriend became pregnant.

“Canelo understood he had to take responsibility and provide for them,” Trejos says. “He had to find an apartment, walk away from school while working in the ice cream parlour and fighting just to make ends meet.”

Balderas adds: “When his daughter was born, he didn’t want her to suffer. So he suffered himself by taking those long hours, sometimes two hours on a bus or train, just to go to the gym and train.

“She was his drive. His main motivation was to not suffer financially.”

Alvarez is now he world’s fifth-richest athlete, but he almost walked away from the sport early in his career. He was earning up to $40 (£32) for his fights, relying on ticket sales for the rest of his purse.

He was persuaded to continue by his friends and family.

“Straight away, you could see he was special,” Balderas says. “He was a young guy and was sparring with the likes of Oscar Larios, who was a world champion who even fought Manny Pacquiao.”

Trejos adds: “I met him in California when he was 18 or 19. What caught my attention was that he was very keen.

“There was a level of security and confidence, a sense of knowing what he had to do, but there was no ego. He didn’t need to tell anyone how good he is.”

‘I could tell within 30 seconds he was special’

On Saturday more than 50,000 will attend Alvarez’s homecoming, taking place over Mexico’s Cinco De Mayo celebration weekend.

But the fighter nor his team were not prepared for the level of fame he has attained.

“I remember once were in a training camp and I told him to open a Facebook account, because that’s the thing everyone is doing now,” Balderas says.

“He said: ‘I’m never doing that. I’m not into this social media.’ Within a year, he had his own team to handle social media.

“He didn’t even realise he would be this famous. He said he wanted to be a great fighter but never felt he would scale to this level.”

Alvarez won his first world title at light-middleweight against Briton Matthew Hatton in 2011.

“Literally within 30 seconds, I knew I was in with someone very special,” Hatton – who lost on points – said.

“When I got over there, I was shocked by the support he had, the amount of fans he had and the amount of media coverage that was around him and around the fight.”

How Alvarez gained a ‘PhD in boxing’

Alvarez, a four-weight world champion, is arguably the biggest draw in boxing.

There is no padded record. He has beaten legends such as Miguel Cotto, Shane Mosley and Gennady Golovkin.

“I just want to continue make history along the way and fighting with the best fighters out there,” he says.

He lost on points to pound-for-pound great Floyd Mayweather in 2013. Aged 23, the inexperienced Alvarez was still learning his craft.

“When he challenged Mayweather we thought he was going to get clobbered. Did he lose? Yeah. But that was the moment he got a PhD in boxing,” Trejos says.

“That is when he turned the corner into understanding what he lacked.”

Last year he was defeated by WBA ‘Super’ champion Dmitry Bivol for the light-heavyweight world title.

Some suggested Alvarez was no longer at his peak. Others commended him, as the smaller of the two fighters, for even taking on the challenge.

“Canelo just takes on all comers and that’s got to be applauded,” Hatton says.

The shy teenager is no more

Alvarez’s personality has flourished in recent years. He approaches his media duties with confidence, and is more willing to engage in trash talk with opponents.

“When I first met him, we didn’t have big statements or crushing words,” Trejos says. “I remember working on his fights and thinking: How are we going to sell this?”

Having always given answers in Spanish, he learned English in an unconventional way by picking it up while playing golf with friends.

Trejos says: “One time, he was criticised for playing golf and competed alongside professionals in a tournament. He said: ‘You’re jealous because I can do both and I can do both well.’

“We are now seeing not just the fighter, not just his personality, but we are seeing the man.”

Alvarez’s business ventures range from his own tequila line to real estate, financial trading and a chain of convenience stores.

But Balderas says Alvarez “always keeps the Mexican people in his heart” through various charity initiatives.

“When the earthquake happened in 2017, Canelo was one of the first people to be on the ground,” Balderas says. “He didn’t just donate money, he was there doing the hard labour.

“There were pictures on the internet and he didn’t like that someone posted it. He doesn’t like to brag.”

A champion who ‘polarises his own community’

Mexico has a rich boxing heritage – and Alvarez’s achievements are earning him a place as part of that. Yet he “has that ability to polarise his own community”, according to Trejos.

She says some do not hold him in the same regard as past Mexican fighters, such as Ruben Olivares, Julio Cesar Chavez, Salvador Sanchez and Juan Manuel Marquez.

Balderas also feels Alvarez is not given the credit he deserves from some Mexican fans, but offers a different reason.

“People want to see blood in Mexico,” he says. “They want to see war, someone who goes out there and brawls. They want that from Canelo.

“They want him to suffer, bleed, go down on the floor, then get up and win. But Canelo is too much of a smart fighter.”

Perhaps Alvarez’s dominance in the ring is to the detriment of his own popularity. Perhaps he will only be appreciated fully by all fans once he hangs up the gloves.

Or maybe a knockout performance in front of his home people on Saturday will secure his legacy among Mexican people.