He was sitting in his flat in his beloved Leith, a smile on his face as he told a story about some recent burglaries in the area.

Ken Buchanan imagined what might happen if the local hoodlums broke into his place, laughing at the thought of them dragging the heavy suitcase out from under his bed and opening it up to find the story of his life.

Some world championship belts. Some photographs of him with Muhammad Ali and Roberto Duran. Some cuttings from around the world documenting his lightning speed, his snapping left jabs and the greatness of his career. His World Boxing Hall of Fame ring.

“I’d love to be hiding behind the curtains as it dawned on them whose flat they were in,” he chuckled. “What a shock they’d have got. They wouldn’t have run out the door, would they? They’ve have been so scared they’d have gone straight oot the windae.”

The great Buchanan – “the out-and-out fighting man” as Hugh McIlvanney once described him – passed away on Saturday aged 77.

The moment the grim rumours hardened to upsetting fact, the tributes started to come in clusters from at home and abroad. Buchanan was of Leith and Edinburgh but, such was his legend, he was a world figure in the fight game, one of the most accomplished fighters the cruellest sport has ever known.

Immediately the mind returned to an afternoon spent in his company in 2015. He was in the back room of a sheltered housing unit in Leith recalling snapshots of his previous life when he was young and fearless.

In this place, Buchanan was just another resident, a man trying hard to free himself from the addiction to alcohol that troubled him more than any of the fearsome fighters he spoke about that day.

The conversation was heavy, then light, then heavy again. He flitted between memories that made him laugh and darker ones that made him cry. This was a compelling man from his top to his toe.

“I tell young guys and young lassies, ‘Watch your drinking because, I’m telling you, it’s killing me’,” he said.

He transported us to the most extraordinary places and recalled the most storied people.

He talked of the night at Madison Square Garden in December 1970 when, as world lightweight champion, he put on a boxing exhibition against the undefeated Canadian Donato Paduano that had gnarled New York boxing scribes comparing him to Sugar Ray Robinson on his best days.

He spoke of fighting on the same bill as Ali, not once but twice, both times at The Garden. The second one was 1972, when Buchanan beat Carlos Ortiz.

“I cannae remember the guy Ali was fighting. Famous, though. Used to be world champion. Wasn’t a huge guy. Big long face,” he said.

The guy he was talking about was Floyd Patterson, one of the most intriguing heavyweights in the history of the division.

That was the thing with Buchanan, though. He was never wowed by any of those guys because he was one of those guys. He was famous in his own right. Respected and celebrated. Revered, even.

“The first time I was at Madison Square Garden was when Ali fought Oscar Bonavena and I fought Paduano,” he said. “I was top of the bill, I was world champion and Ali wasn’t world champion at that stage. He hadn’t won back the title yet.

“I had a dressing room and he didnae so Angelo Dundee [Ali’s trainer] comes up and says, ‘Can Ali share your room?’ and I said, ‘Aye’.

“There was an ashtray with a piece of chalk in it so I took a piece of chalk and I bent down and I made a mark on the wooden floor across the way and when I got to the end Ali is standing there, saying, ‘Hey man, what are you doing?’

“And I says, ‘Muhammad, this is my dressing room, right? And I’m letting you share it’. He says, ‘Yeah. What’s the line for? I said, ‘That’s your side and this is my side and if you dare cross that line…’

“I showed him my fist and he did that tight-faced thing and burst out laughing. I thought, ‘Thank God, he saw the funny side, he’s not going to batter me’.

These were the stories that Buchanan told for the rest of his life. Ali, Paduano, Roberto Duran, Jim Watt – and most especially Ismael Laguna and the day the Scot announced himself as a world champion.

It was September 1970 at the Hiram Bithorn Stadium in San Juan, Puerto Rico. “I did 15 rounds with Laguna in 125 degrees of heat at two in the afternoon. Laguna was the champion and he thought I’d go down the Swanee dead easy with the heat and everything.

“He spoke to me years later through an interpreter. I met him at the Hall of Fame when I became the first living British boxer to get in there. He said that he expected me to collapse after eight or nine rounds. He said, ‘When I hit the 11th and 12th I kept saying to my manager: What’s keeping him up?'”

Laguna hadn’t done his homework on the indomitable force he was facing.

On that day of the chat in 2015, and on many other days besides, Buchanan spoke to us about his life and times, how he got bullied a wee bit at school, how he was small and skinny and had a chip on his shoulder.

Kids of his own age fought him and, when he put them away, their older brothers fetched up for a fight. They went down, too. “They’d start arguing with me and it was a left jab I gave them – and that was it. There weren’t many big scraps. It was just one punch.”

That feeling of being targeted never really left him throughout his life, he said. He always admitted that. It wasn’t always easy being around him. He knew that better than anybody.

But what greatness lurked within him. In the two years between autumn of 1970 and autumn of 1972, Buchanan fought at The Garden five times. In his career he fought at the Miami Beach Convention Center, where Ali beat Sonny Liston in 1964, the Royal Albert Hall and the Cagliari football stadium.

He fought in South Africa, Japan, Italy, Denmark, France and Spain. He fought in Nottingham and Solihull, Hamilton and Port Talbot, Leeds and Glasgow and Aberavon.

And yet he never fought in his home town. “The Edinburgh people have always been fantastic to me, but the people who ran Edinburgh just weren’t aware of boxing,” he said. It was a source of sadness and frustration for years. A hometown great without any lasting tribute to what he achieved on the world stage.

All of that changed in 2022 when the driven folk at the Ken Buchanan Foundation raised the money for a magnificent statue in his honour, now sitting proudly on Leith Walk.

Buchanan was there. Suited and booted, bow tie, big smile, pride all over his face. It must have been a joyous day. Belated but glorious.

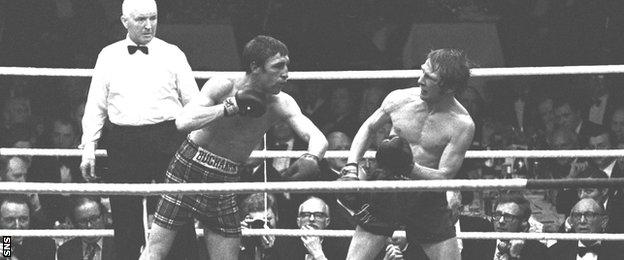

Sixty-nine professional fights and 555 rounds of boxing and yet so often it comes to one round in particular, the 13th against Duran and the late and low blow to Buchanan’s “watcha-ma-callits” that ended that fight, albeit while Duran was well ahead on all scorecards on the night.

“He was a scrapper,” Buchanan said. “I made the mistake of trying to go toe-to-toe with him. Stupid. I should have hit and run, hit and run.”

The respect that Duran had for the Scot was vast. There was supposed to be a rematch but Duran’s manager was having none of it. Too dangerous.

Whenever Duran was asked to name the toughest opponent he ever faced, Buchanan was always in the conversation with Sugar Ray Leonard, Thomas Hearns and Marvin Hagler. On plenty of occasions, Duran said that Buchanan was the best he ever faced.

He had other big days after that Duran fight in 1972 – Watt a year later was an epic – but the troubled times started to mount in his life outside the ring. His marriage broke down, his house was sold, the hotel that he owned went, too. He had money and he was too trusting with people and he lost it. Latterly, dementia came for him.

What will never fade is the memory of him in his pomp. In a documentary a few years back, Buchanan looked back on his days in the ring. “I’ve had my life and I’ve had a good kick of the ball,” he said. “I’ve no axes to grind. I’m just Kenny Buchanan. I was a world champion.”

Not just a world champion. Buchanan was one of the greatest champions this country has produced in any age, in any sport, ever.