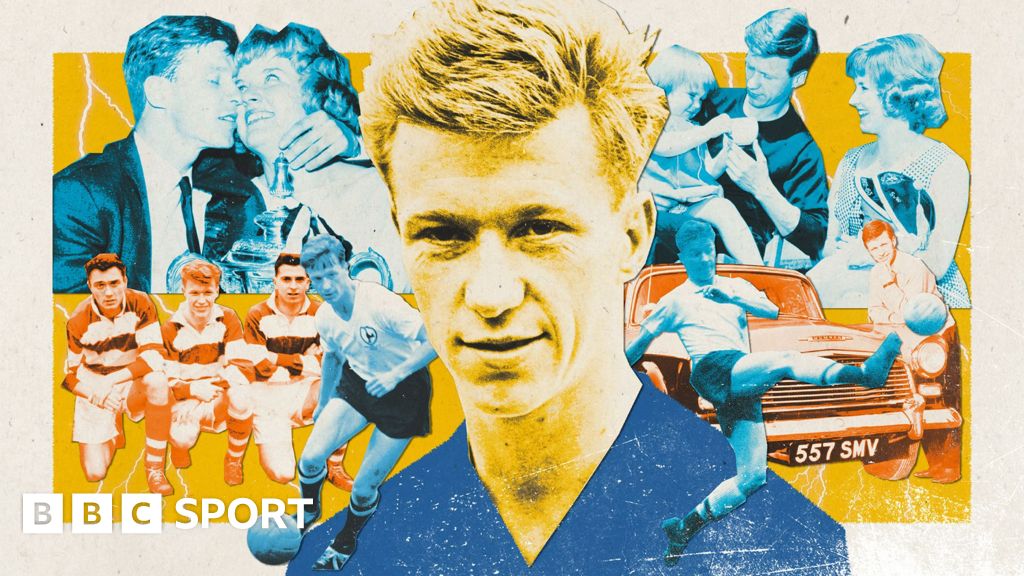

Too often, though, the character lacked depth: as thin as the page of the comic he seemed to spring from.

“He was this kind of Roy of the Rovers figure and as I got older I got frustrated and almost embarrassed by people having a better knowledge of my dad than I did,” Rob says.

“Part of the joy of having a father is finding our own identity – there is a little blueprint there and if we are lucky we follow the good bits and jettison the bad bits – but I didn’t have that.

“There is still a kid in me that wants to know the simple stuff: what he smelt like and sounded like, a bit more about him, rather than this persona. That is the eternal frustration.”

Rob channelled that frustration into a book – The Ghost of White Hart Lane – interviewing family members, former team-mates, friends and acquaintances, to try and discover the man behind the myth.

And gradually he found him.

Rob heard about the sadness and homesickness that would grip John each winter in London. He heard about the time he drove home dangerously drunk, clipping the White Hart Lane gates in his car. Most revealingly, an uncle told Rob about the child that John had fathered in Scotland and left behind before he travelled south, played for Spurs and met Sandra.

“Part of me has always been trying to live up to this person who was absolutely perfect, who was idolised not just by the family, but by hundreds of thousands of people,” says Rob.

“To find out he had defects and weaknesses, that he struggled with confidence, mental health and seasonal affective disorder, that he had made mistakes – if I had found all that out earlier, it would have made more sense to my life.

“If we know our parents are fallible, it really makes us understand that we can make mistakes. We don’t have to know all the answers.”

John’s absence shaped Rob as surely as his presence would have.

Rob is a still-life photographer – “I have always been looking for those details and clues” – and is also training as a counsellor.

Later this month, he will be in the audience at Tottenham Hotspur Stadium for the first performance of a play he has helped produce about his father’s life.

“It is something I talk about with my own therapist,” he says. “Having seen life breathed into the story at the read-throughs, it reinforced the reasons I wanted to get involved with the project.

“I think there is something of trying to bring my dad back to life.”

After two nights in Tottenham, the play will then transfer north, taking the opposite journey to the one John took in life, for a stint at the Edinburgh Festival.

There are some things that remain lost. Rob is still searching for a recording of John’s voice. One of his match-worn Tottenham shirts remains elusive.

But over the decades, he has found much more: an understanding and an empathy for the father he never knew.