Abe Mitchell’s life did not get off to the best of starts.

But the illegitimate son of Mary, born in an East Grinstead workhouse in Victorian England, would become one of the highest-paid sportspeople of his era and go on to be immortalised as the figure that sits atop the Ryder Cup.

The ‘Cantelupe Crack’s’ story truly is a rags to riches tale.

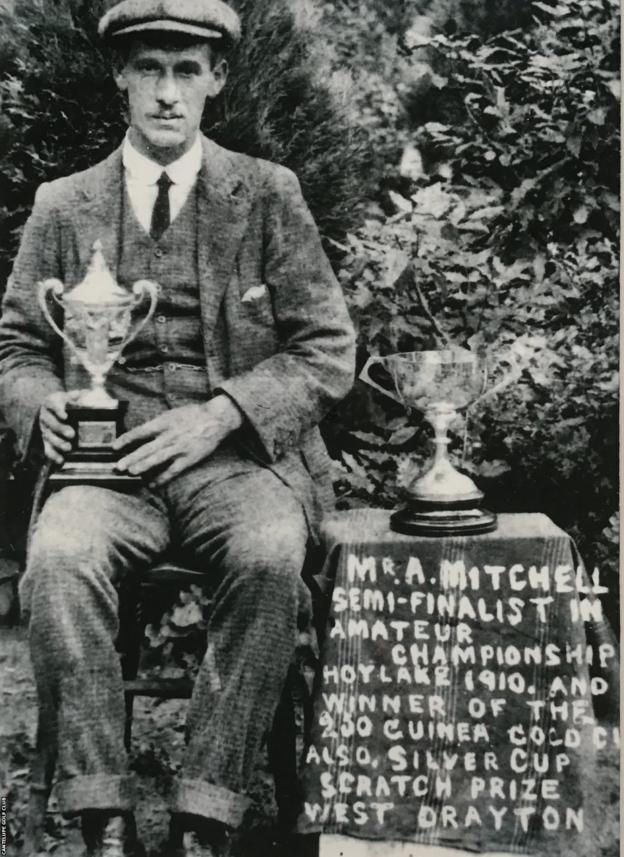

As a boy, he carved his own clubs from branches lopped from trees to hit balls found in the undergrowth. He was pilloried as an artisan golfer, a “workman” infiltrating a gentleman’s domain, after winning his first significant title in 1910.

He served on the front line in World War One and would later suffer with anxiety on the course. Sadly, he would never win a major, ending up being dubbed the “greatest player to never win The Open” by five-time champion JH Taylor.

Mitchell was born in January 1887 and his golfing journey began at the age of three, when he drifted out on to the fairways of Royal Ashdown Forest, which itself was in its infancy, having only been founded a year after his birth in 1888.

The course, sculpted from common ground owned by the seventh Earl De La Warr on the edge of the village of Forest Row in East Sussex, was not to everyone’s liking. It attracted walkers refusing to give up their right of way, while smallholders would damage greens.

To broker peace, the vastly richer members of the golf club unanimously voted to try to get these commoners onside. The result was the formation in 1892 of the artisan Cantelupe Club – named after Viscount Cantelupe, the Earl’s son.

It is now the oldest surviving artisan section in England and current Cantelupe captain, Max Pearson, told BBC Sport: “It was a club for local people, who had to live within a five-mile radius of the village, although nowadays it is within four miles of the church spire.

“The artisans were recruited as the original greenstaff and they were rewarded with free golf.”

It was perfect for Mitchell and his relations, whose humble beginnings would have prevented them from playing on their local course. He was one of four brothers and seven cousins and uncles who started out as Cantelupe members, and all would go on to become greenkeepers or professionals.

“They could turn out a team of Mitchells and slaughter Oxford or Cambridge university teams,” says Colin Strachan, a Royal Ashdown Forest member since 1978, who has written a book detailing the storied history of the club – Fair Ways in Ashdown Forest.

“By the age of eight, Abe was fashioning his own clubs out of branches taken from beech trees to hit balls that he found on the course.

“By the age of 12 he was out playing with, and beating, adults.”

Pearson said that in 1910 Mitchell was “commended to the England team to face Scotland by AG Hutchinson, a man he had beaten four times in annual matches that pitted the artisans against the members of the club”.

It would cost Hutchinson his place in the side and Golf Illustrated called Mitchell’s selection “the advent of the working man of the ancient and honourable calling of gardener”. The publication also sniffily suggested the match featured “the cream of gentleman golfers, and Abe Mitchell”.

He would further defy his critics the same year, by winning the prestigious Golf Illustrated Gold Vase at Sunningdale, and again in 1913 at Walton Heath, as his stock rose in the game.

Golf Illustrated was again derisory in its reporting, describing Mitchell as “a gardener from a working man’s golf society with playing rights at Royal Ashdown”, adding it had “never seen a workman play before”.

It led Mitchell to say “golf is the game of classes in England and it is my fair conviction that artisans are not wanted”.

But his exploits had brought him to the attention of Sir Abe Bailey, a South African diamond merchant and huge sports fan, who played a significant role in the formation of the International Cricket Council.

Bailey had an enormous house overlooking Forest Row and had been keeping a close eye on Mitchell’s progress. He paid him a retainer to be his playing partner, thus benefiting from winning money in betting matches, while also employing him as a gardener and chauffeur.

Mitchell would enjoy his joint highest finish at an Open Championship in June 1914, finishing in a tie for fourth at Prestwick as the legendary Harry Vardon completed his record sixth triumph in golf’s oldest major.

But the outbreak of World War One the following month cruelly interrupted his career.

“Abe spent much of the war on the front line in northern France, pulling horses, which were, in turn, pulling huge guns through the mud,” says Strachan.

“Golf courses were turned into trenches as training grounds for the Somme, and remnants are still visible at Royal Ashdown.

“Training for soldiers usually lasted a fortnight, then they all went to church on the Sunday before being loaded into cattle trucks. The whole village of Forest Row would turn out to watch them depart down the hill from the club.

“Abe was as strong as an ox and one of the lucky ones to survive.”

Mitchell had been renowned as one of the longest and straightest hitters and when The Open returned in 1920 at Royal Cinque Ports in Kent, he surged into a six-shot lead after the opening two rounds on 30 June.

But he struggled in the following morning’s third round, posting an 84 as his lead evaporated and he would eventually finish fourth, four behind Scotland’s George Duncan.

His friendship with Duncan would prove lucrative though. In 1922, the pair went on a whirlwind tour of the US and Canada that earned them at least $25,000 each, worth about £370,000 today.

Details of the length of the trip are a little sketchy but Strachan believes it would have been around three months.

“They were playing for literally shedloads of money,” he says. They would play two rounds a day and squeezed in 84 rounds, playing as far north as Winnipeg in central Canada, to Florida in the south and visiting places in between such as Kansas, Milwaukee and New York.

“They won 51 of the matches, losing a few times to the great Walter Hagen (who won 11 major titles) and a couple to the emerging Gene Sarazen (who would win seven majors).

“They returned in 1925, with Hagen the backer and again being given $25,000 each and certainly topping that up by winning bets on matches.”

By this point, Mitchell had met Samuel Ryder, the wealthy seed merchant who would go on to found the transatlantic tournament that bears his name.

Ryder, who only took up golf at the age of 50 following medical advice to seek more fresh air and exercise, lived in St Albans, just north of London.

He joined the city’s Verulam Golf Club and sponsored golf tournaments, which led to him meeting and employing Mitchell as his personal coach, paying him a salary of £500 a year, plus covering his expenses to play in other tournaments.

Mitchell was due to play in the inaugural 1927 Ryder Cup at the Worcester Country Club in Massachusetts but reports at the time said he was unable to make the journey because he had a bout of appendicitis.

Strachan disputes that claim, saying: “I believe it was a manifestation of his anxiety that stopped him from travelling.”

Mitchell would go on to play in the next three Ryder Cups, helping Great Britain to defeat the US on his first appearance in 1929 at Moortown in Leeds and again at Southport & Ainsdale in his final outing in 1933.

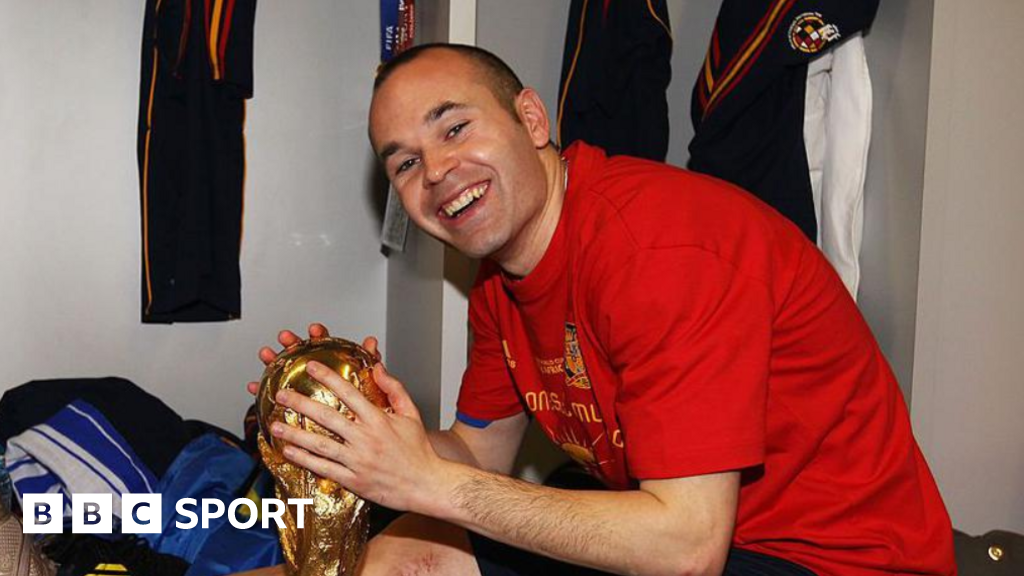

The 17-inch high gold trophy that the teams still play for was donated by Ryder, and as a thank you to Mitchell for teaching him the game, he had a figure of his coach placed on top.

“I owe golf a great deal,” said Mitchell. “What you have done, putting me on top of the cup, is more distinction than I could ever earn.”