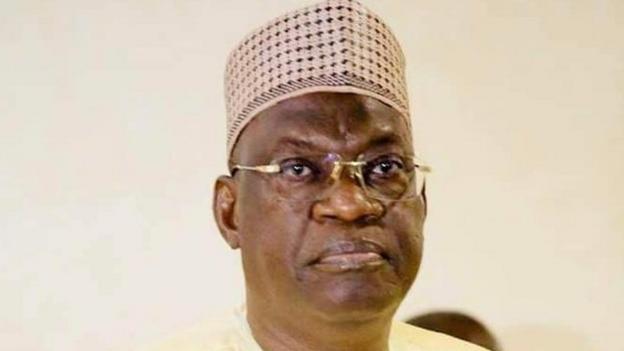

On Tuesday, a football election like few others will take place in Mali when the one-and-only candidate, the current president of Mali’s football federation (Femafoot), looks set to win a four-year term from a prison cell.

Mamatou Toure, widely known as Bavieux, is currently in jail in the Malian capital Bamako as he awaits trial after being accused of embezzling funds during his time as a financial and administrative director in Mali’s National Assembly.

The 66-year-old, who has led Femafoot since 2019, is a member of both the Fifa Council, the board of football’s world governing body, and the executive committee of the Confederation of African Football (Caf).

He is also the sole candidate for the elections after being the only one of four men to pass an eligibility test, which he managed to do prior to being indicted on 9 August by the Malian state for “attacking public property as well as forgery and use of forgery and complicity”. Along with four others, Toure is accused – in charges that all deny – of embezzling a reported US$28 million from the state purse.

Toure is a former tax inspector with a master’s degree in auditing. The charges against him cover a period between 2013 and 2019, when the five representatives of the then ruling RPM (‘Rassemblement pour le Mali’) party were in power, and which largely pre-date Toure’s election as Femafoot president in August 2019.

On the eve of Tuesday’s elections, BBC Sport Africa can highlight a series of financial gaps that have taken place within Femafoot under the administration of Toure. While hundreds of thousands of dollars remain unaccounted for, so several of Mali’s national team trainers have complained about going unpaid for many months.

Financial questions

An audit conducted into Femafoot’s finances of 2022, conducted by the Pyramis group and dated March 2023, which has been seen by the BBC, shows that Femafoot did not pay any taxes to the Malian state regarding its employees.

“Femafoot deducted taxes and duties from staff salaries for a total amount of CFA 23,9m [just under $40,000],” the audit stated. “Femafoot did not declare or pay these taxes and duties.”

The tax failure was not new, since an audit into Femafoot’s financial affairs of 2020 (covering January-September) had also found it did not pay the country’s inland revenue ‘all the tax deductions it retains on salaries paid to its staff’. That same 2020 audit (conducted by the Cabinet Ficogec group) also stated that key financial and management reports had gone missing.

In addition to the tax issue, the March 2023 audit showed that nearly $50,000 were awarded to unspecified ‘other parties’ without any reason given nor any approval agreed by Femafoot’s board for the payments – in direct contradiction of the body’s statutes. When sports equipment was sold for just over US$300,000, US$138.5k was registered in Femafoot’s account and US$144k was paid – in cash – to MK Productions, the company reported as providing the sports kit, so leaving US$22k unaccounted for.

Without receiving documents relating to the sales, with the auditors citing no inventory not itemised sales, Pyramis declared themselves ‘unable to comment on the correct valuation of the sports equipment sales’. The BBC can find no record for a sports company called MK Productions within Mali – where the only-registered company with that name works in media, not sportswear.

The questions raised in the 2023 audit follow a theme from 2022, when a document signed by 44 Malian football officials – nearly all of whom were presidents of clubs, including some of the country’s top sides – also raised several financial concerns.

One of these was how Femafoot spent nearly US$1.25m in the final quarter of 2020, despite none of this being presented to the federation’s executive committee for approval (while also questioning why this quarter was not covered by Cabinet Ficogec’s 2020 audit).

Addressed to Mali’s then political rulers, the document also queried what Femafoot had done with the $790,000 it received from Caf regarding the country’s participation at the 2021 Africa Cup of Nations, money that should have been refunded to the Malian government since the latter finances the country’s national football teams.

Finally, no financial report has been presented to Femafoot’s general assembly, where all its members gather, for the past three years, which contravenes Fifa statutes. The BBC has sent questions regarding all the financial issues outlined above to Femafoot but has yet to receive a response.

Sole Candidate

Despite the serious pending charges against him, Toure is the sole candidate for Tuesday’s Femafoot presidential election – after three others failed to pass the eligibility test. One candidate, former Femafoot media spokesperson Salaha Baby, did initially pass, but Toure successfully appealed his eligibility to rule him out of the race.

“The disqualifications of our candidacies follow a multitude of fanciful procedures by the armed arms of the Femafoot president,” Sekou Diogo Keita, a former vice-president of Femafoot, told BBC Sport Africa.

“Why is no one taking any action? The only candidacy validated is the one of someone actually jailed.”

Keita, who has written to Fifa to complain about the ongoing process as well as Femafoot’s financial affairs, is currently serving a five-year ban issued by the Malian football body in 2022 on charges he describes as politically-charged. Meanwhile, Femafoot has failed to answer a question about showing bias towards its current president when asked by the BBC.

Toure’s would-be rivals have appealed his eligibility – arguing, among other matters, that he should have declared the pending state investigation into him when filling out his eligibility form for the Femafoot post.

“Are you currently the subject of a disciplinary, criminal or civil procedure or investigation?” asks one of the questions on the Femafoot eligibility form.

Toure’s rivals believe he either failed to accurately answer the above question or simply did not fill in any form.

On 15 August, Baby formally wrote to sport’s highest court, the Court of Arbitration for Sport, to appeal against Toure’s candidacy and request the reinstatement of his own.

“Being a member of the Fifa Council cannot spare Mamoutou Touré from the good governance protocol established by your body,” wrote Keita to Fifa Secretary General Fatma Samoura.

In response, Fifa – which is sending emissaries to oversee Tuesday’s vote, as are Caf – said it “has been closely following the electoral process”.

“Any dispute concerning the electoral process should follow the established legal procedures,” the governing body added. “Please note that all Fifa Forward projects undergo an annual central review by Fifa.”

Further Fifa ban feared

Keita was the second Malian to write to Samoura on 15 August, after Mali’s Sports Minister Abdoul Kassim Ibrahim Fomba also wrote to the Senegalese to ask for help overseeing the elections, citing a “real urgence”.

“The candidates have identified specific points of violations of the texts, which, according to our reading, are likely to call into question the whole process and make us relive a new crisis in football,” Fomba wrote.

Fomba was mindful not to be seen as interfering in the federation’s affairs, given that Fifa set up a Normalisation Committee to run Femafoot in 2017 to revise statutes and conduct elections after it banned Mali following government interference in the running of its football.

The threat of a further Fifa ban for governmental interference has also prevented Keita from filing a lawsuit against those running Femafoot – and how they have used funds, including those received in annual grants from Fifa – in the Malian courts.

“We did not go to the civil court because Femafoot always tells everyone that as this is money from Fifa, no one can interfere with how it is spent – even the state,” he told BBC Sport Africa. “They use this argument every time.”

In response to the indictment against Toure, a Femafoot statement on 10 August said his arrest was ‘fuelled by Toure’s opponents’ while stressing the ‘presumption of innocence’.

Meanwhile, it is unknown how long Toure will be in jail pending trial, with one Malian journalist telling L’Equipe this month that “pre-trial detentions in Mali can last a long time – there are cases of people suspected of corruption who have been in prison for two-three years as they await trail”.

On the pitch, Mali are preparing for January’s Africa Cup of Nations in Ivory Coast while its Under-23 team will contest the Paris Olympics this time next year.