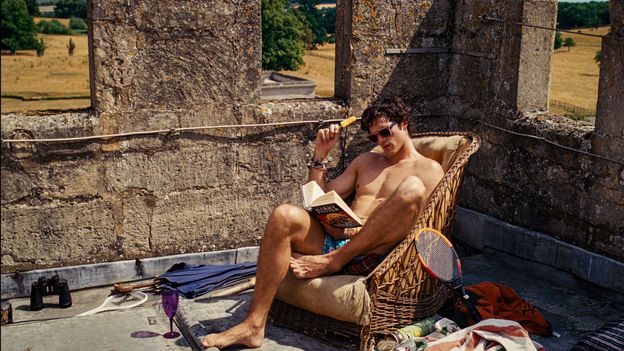

The Archers’ script recasts Colonel Blimp as Major-General Clive Wynne-Candy, introducing him in then-present-day 1943 as the familiarly rotund and moustachioed caricature from Low’s drawings. An extended flashback then moves 40 years into the past, finding Candy as a youthful subaltern on leave from the Boer War, Victoria Cross gleaming on his chest. Tracing this soldier’s life over the subsequent four decades, three wars, and two doomed romances, Powell and Pressburger explore how Candy’s reactionary worldview is shaped and calcified by his experiences as an unquestioning servant of the British military. As Powell wrote in a letter to the actor Wendy Hiller, reproduced in Ian Christie’s edited edition of the film’s screenplay, “Blimps are made, not born. Let us show that their aversion to any form of change springs from the very qualities that made them invaluable in action; that their lives, so full of activity, are equally full of frustration…”

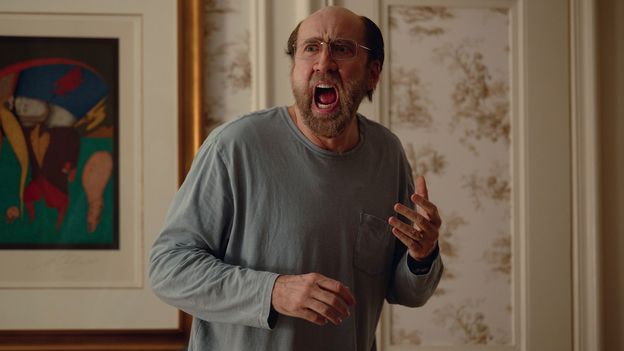

The establishment upset

Authorities at the Ministry of Information and the War Office were dismayed by the project and refused any official support. According to SP Mackenzie’s book British War Films 1939-45, Secretary of State for War PJ Grigg wrote to Powell in June 1934, “I am getting rather tired of the theory that we can best enhance our reputation in the eyes of our own people or the rest of the world by drawing attention to the faults which the critics attribute to us, especially when, as in the present case, the criticism no longer has any substance.” A summary of the script found its way to Prime Minister Winston Churchill, who wrote to Minister of Information Brenden Bracken, “Pray propose to me the measures necessary to stop this foolish production before it gets any further.”

“Churchill sometimes got a bee in his bonnet about things he didn’t fully understand,” Richard Toye, Professor of History at the University of Exeter and author of Winston Churchill: A Life in the News, tells BBC Culture. “He quite often had harsh, repressive instincts when it came to the media, but he didn’t always follow them through, and other people stood in his way to try to make him see sense.”

Indeed, Bracken was uncomfortable with Churchill’s request, and responded that he had “no power to supress the film”, warning that “in order to stop it the government would need to assume powers of a very far-reaching kind”.

“Bracken’s line was that British propaganda was geared towards the differences between democracy and dictatorship, and that to suppress the film would have been the sort of thing the Nazis did,” James Chapman, Professor of Film Studies at the University of Leicester and author of The British at War: Cinema, State and Propaganda, tells BBC Culture. “A democracy, even in wartime, has to be strong enough to allow the expression of dissenting voices.”