The eight must-see exhibitions of 2020

(Image credit: Getty Images)

From Raphael to Yayoi Kusama, Kelly Grovier picks the art you can’t afford to miss in the coming year.

A

A great art exhibition can alter forever not only the fortunes and reputation of the show’s subject but the lives and imaginations of those who absorb its wonders. 2020, a year whose very numerical formulation suggests a clearness of vision, is shaping up to be both an eye-opening and mind-expanding marathon of back-to-back visual treats. From New York to Paris, Oxford to Madrid, here are the shows whose hype is justified.

More like this:

– The most striking art of the 2010s

– What courage really means in art

– The images inspired by protest

One could weep for grief wondering what the mighty Renaissance master Raphael could have gone on to create in maturity had he not died in 1520, aged just 37. To mark the 500-year anniversary of his untimely death, a host of shows have been organised around the globe – from a full-scale retrospective at the National Gallery in London to the unveiling of a freshly conserved preparatory cartoon for the artist’s best-known work, the Vatican fresco School of Athens (1509), at the Veneranda Biblioteca Ambrosiana in Milan. To pay homage to Raphael’s genius in recognising the crucial role that printmaking can play in promoting an artist’s vision, the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC will dust off for display (beginning 16 February) an extraordinary trove of prints and drawings by both the artist himself and by his renowned contemporaries. Among these collateral wonders is Ugo da Carpi’s chiaroscuro woodcut, David Slaying Goliath, which is based on a design by Raphael in the Vatican. The work demonstrates both Raphael’s virtuosity as an image-maker and Da Carpi’s inventiveness as a printmaker.

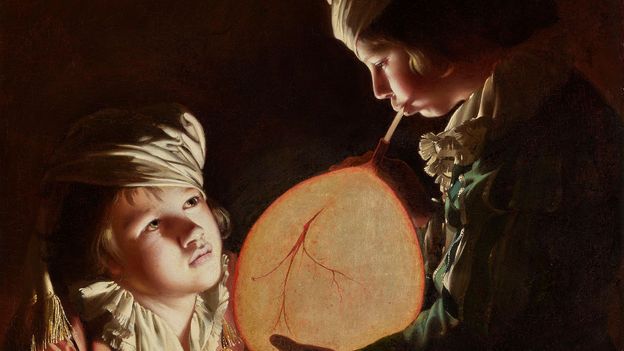

Based on a design by Raphael, Ugo da Carpi’s David Slaying Goliath (c 1520-27) was one of the first examples of woodcuts in “light and dark” (chiaro et scuro), or chiaroscuro

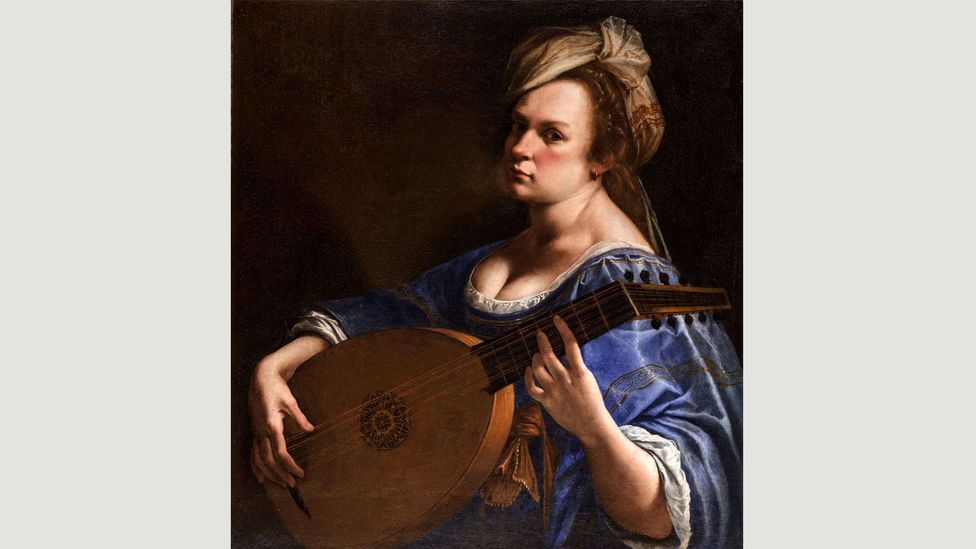

In April, London’s National Gallery is showing the UK’s largest-ever survey of the work of the extraordinary Italian Baroque painter and trailblazing female artist Artemisia Gentileschi. The first woman to be admitted as a member of Florence’s exclusive Accademia delle Arti del Disegno (the artists’ academy), Gentileschi was recognised for her inventiveness, particularly in the fashioning of allegorical scenes and innovative self-portraits. Among the three dozen works by Gentileschi to be summoned from far-flung international collections is the hypnotising Self-Portrait as a Lute Player, which depicts the artist, fingers poised, in mid-strum, plucking the mystery of her own existence from a sombrous hum of fretful shadows.

Self-Portrait as a Lute Player (1616-18) will be one of the works on display at the National Gallery show, which covers Gentileschi’s training in Rome and her time in Naples

In February, the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, England, is holding the first major exhibition ever staged in the UK devoted to the early years and work of Rembrandt van Rijn, perhaps the most adored of all the Dutch masters. The show, Young Rembrandt, promises to take visitors from the earliest-known scribbles made in the 1620s to the breakthrough works of the following decade, which permanently propelled him into popular imagination. The ambitious exhibition (which will feature more than 130 works, including 34 paintings by Rembrandt and 10 by noted contemporaries), will see the first public display of a newly-discovered painting from this formative period, Let the Children Come to Me (1627-28), created when Rembrandt was in his early twenties, with a newly-attributed self-portrait of the fresh-faced young artist staring out at us in awe.

The Ashmolean exhibition begins with Rembrandt’s earliest-known works made in his native Leiden in the mid-1620s, including this self-portrait from 1629

2020 promises to be more than just a platform from which great works from the 16th and 17th Centuries will be brought into sharper focus. For art enthusiasts keen to measure the impact on today’s consciousness of a more modern master, the unveiling in Paris of a new major installation by the Bulgarian-born environmental artist Christo is likely to be among the year’s highlights. For 16 days beginning on 19 September, the city’s iconic Arc de Triomphe will be completely swaddled in 25,000 sq m of ghostly blue polypropylene fabric cinched tight by 7,000 m of scarlet rope, transforming the familiar monument into something startling and strange. The ephemeral work will echo the artist’s era-defining Wrapped Reichstag, 1995, and comes 35 years after he – along with his wife and long-time collaborator Jeanne Claude (who died in 2009) – wrapped the Pont Neuf in Paris.

Wrapped Reichstag was a project Christo had begun imagining in 1971 with Jeanne Claude (Credit: Alamy)

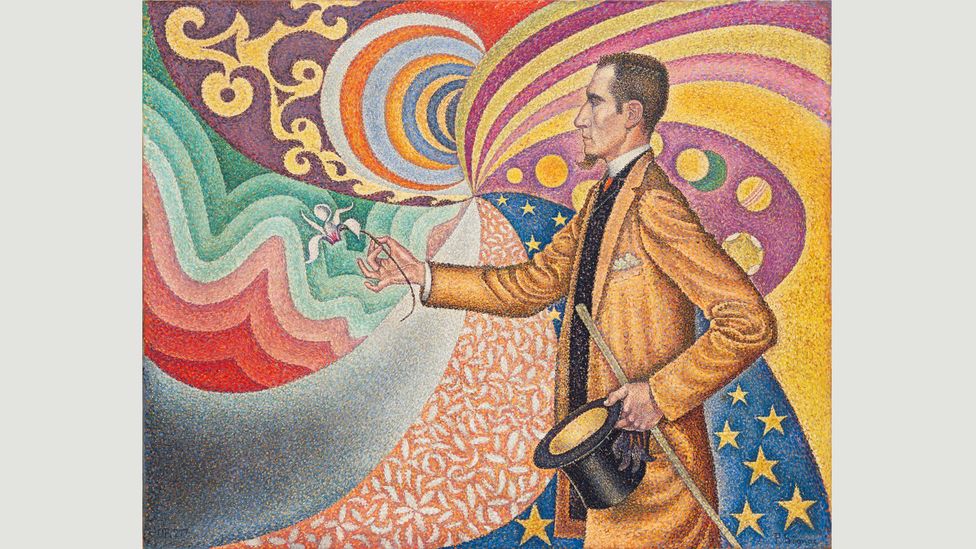

If you think Christo is performing a subversive assault on Paris by hiding one of its most cherished spectacles under acres of plastic, you’d be placing him in an illustrious lineage of art-world figures accused of mounting assaults on the city. In 1894, the avowed anarchist and art critic Félix Fénéon, the subject of what promises to be a fascinating exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York (beginning in late March), was charged with planting a bomb in a flowerpot in a fashionable Paris hotel restaurant. Fénéon was crucial to the rise of Post-Impressionist painting and is responsible for coining one of the terms by which we know those little dots and dabs of paint we associate with such artists as Georges Seurat and Paul Signac: ‘Neo-Impressionism’. Featuring more than 150 works that he championed and admired, the show will explore how Fénéon’s vision of art helped blow modern sensibilities to smithereens.

Fénéon was an elusive figure; he refused Paul Signac’s requests to paint his portrait until 1890, when he agreed as long as it showed his full face – Signac instead did a profile

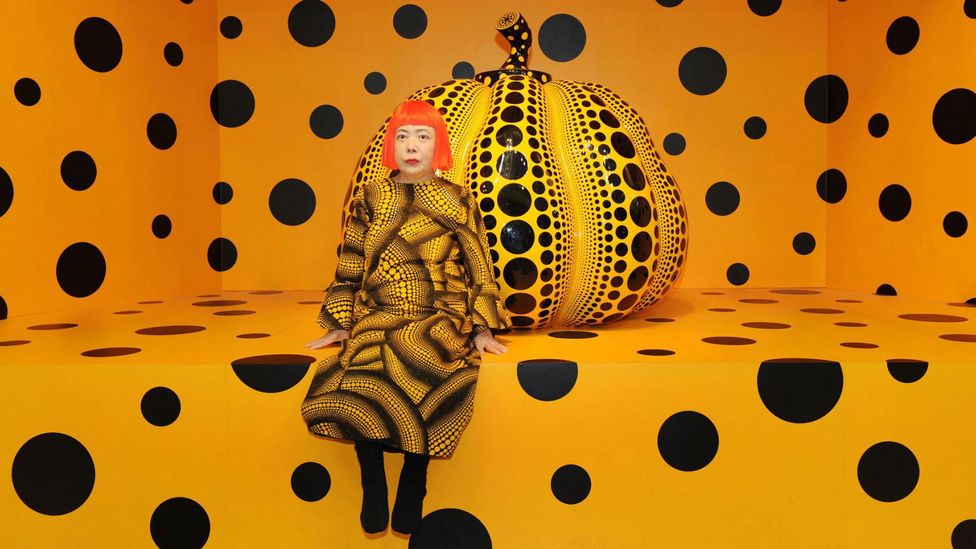

If breaking the world down into a mesmerising blizzard of atomistic dots, as the Neo-Impressionists did, appeals to you, it’s worth taking a note of the launch in May of an ambitious display at the New York Botanical Garden of the work and vision of the contemporary Japanese artist, Yayoi Kusama – famous for her trancing polka-dotted sculptures and installations. Kusama’s fascination with spots and flowers can be traced back to hallucinatory visions she experienced as a child. Occupying the NYBG’s sprawling landscape and encompassing buildings, the ‘multisensory presentation’ will include embodiments of the artist’s well-known mirrored environments, biomorphic collages, paintings, sketches, and even a greenhouse exhibition, in addition to her signature polka-dotted sculptures of natural forms.

Kusama’s works were inspired by visual hallucinations she had in childhood (Credit: NYBG)

You never forget a Marina Abramović exhibition. Visitors to a show she staged in Bologna in 1977 were made to enter the gallery by squeezing through a doorway flanked with naked bodies (her own on one side and that of her partner at the time, Ulay, on the other). Awkward. Before that, the Belgrade-born artist made audiences squirm as she sliced the shape of a star into her stomach with a knife and whipped herself senseless while lying on a block of ice. More recently, she dared gallery-goer after gallery-goer to stare into her eyes for as long as they could bear it. She lasted 736.5 hours. Survivors of the experience started support groups. What, exactly, will be on display at the Royal Academy of Arts in London when Abramović stages a 50-year survey in September (Marina Abramović: After Life) is anyone’s guess. Rumour has it that the ‘living doorway’ is likely to be back in action.

For her 2010 performance The Artist is Present, Marina Abramović met the gaze of strangers at MoMA – many of whom were moved to tears (Credit: Getty Images)

Thirteen years before Andy Warhol sensationally asserted “I want to be a machine”, Belgian Surrealist René Magritte envisioned the emergence of an extraordinary array of automated contraptions capable of cranking out any commodity that modern culture could possibly want – an inventory of make-believe engines that included a “universal machine for making paintings”. Seventy years later, the Thyssen-Bornemisza museum in Madrid is exploring the implications of the Surrealist’s dream through the assembly of 65 canvases, photographs and films that, together, comprise ‘The Magritte Machine’. By breaking down Magritte’s imaginary engine into six component parts – the museum, the silhouette, the window, the mechanism, mimicry, and the mask, which erases and projects the face – the show’s organisers hope to scare up the ever-evasive ghost in the machine of genius.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.