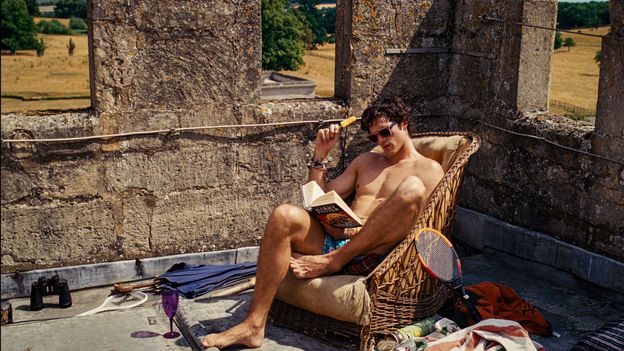

Oliver immediately gets a guided tour, Felix wheeling through libraries and endless colour-coded rooms, up and down staircases and along echoing halls where various “dead relly[s]” stare down from the walls. In less of a nod than a jabbed finger to the film’s own forebears, Felix drops in a mention of Evelyn Waugh being reputedly obsessed with the place. All of this is a calculated set-up, Saltburn intended to seduce the viewer with grandeur as much as it might hope to imply ominous things lurking under the surface.

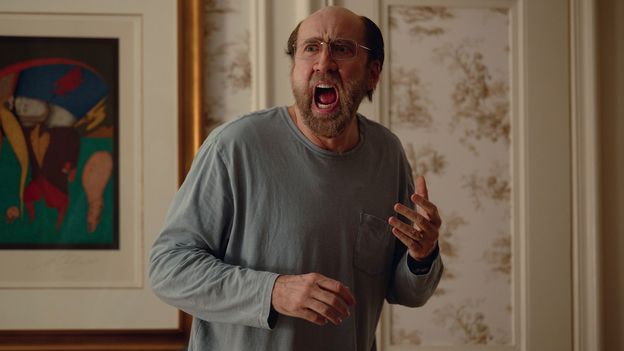

The stately home has long exerted a compelling hold – part-charmed, part-tragic – over the British imagination. It’s a hold that Fennell’s film both wants to subvert and unabashedly tap into. From the works of Jane Austen and novels including Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited (1945), D H Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover (1928), Nancy Mitford’s The Pursuit of Love (1945), Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca (1938), and Ian McEwan’s Atonement (2001) to costume dramas such as Downton Abbey and Bridgerton, there’s a particular narrative allure to houses full of secrets and staff quarters. The big country house lends itself especially well to romances, whodunnits and gothic drama, a combination of beauty, scale and isolation, as well as bizarre inhabitants, providing apt settings for both the lightest and darkest of themes.

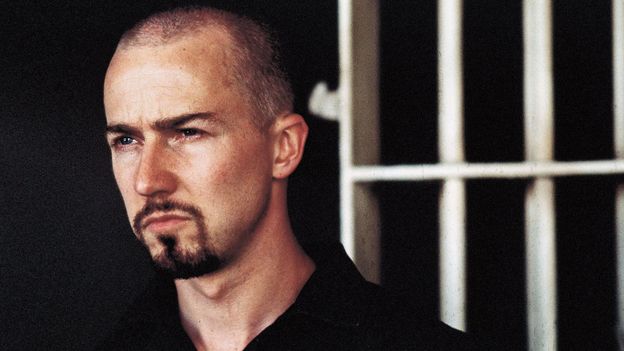

Like those many works before it, Saltburn plays with the idea that these enormous bastions of privilege and power are unique breeding grounds for strangeness – and, crucially, magnets for it too. Cut off both physically and financially, eccentricity and emotional indifference can flourish behind the gates. However, as with those other works, its characters pale by comparison to the generations of real-life aristos who have populated the country’s 600 or so stately homes over the centuries.

The most eccentric owners

Take William John Cavendish Scott Bentinck, the fifth Duke of Portland, a 19th-Century recluse who turned his home Welbeck Abbey in Nottinghamshire into a warren: painting most of the rooms pink and constructing an elaborate system of tunnels beneath the property that stretched to 15 miles (24km), connecting his house to the nearest train station. Or Sir Tatton Sykes, a baronet who loathed flowers with such a passion that on moving into Sledmere House in Yorkshire in 1863, he decreed that every single one be destroyed – including those in the gardens of the village that also sat on the estate. Or Gerald Hugh Tyrwhitt-Wilson, the 14th Baron of Berners, who dyed the feathers of his pigeons in bright colours, took afternoon tea with a pet giraffe, and drove around the estate of Faringdon House in his Rolls-Royce wearing a pig’s mask to scare the locals.