As the writer So Mayer explains, this was a contradictory moment. “What’s happening in the early 1990s is the crest of a wave that starts in the squats and protests of the 1970s,” Mayer tells BBC Culture. “Queer experimental art was being made in the face of institutionalised and culturally prevalent homophobia. Orlando’s conceptualisation starts in the heart of neoliberalism and Thatcherite destruction.” With its luscious historical imagery, Potter’s film might look like an escapist fantasy, but it is littered with topical references to this very specific socio-political moment.

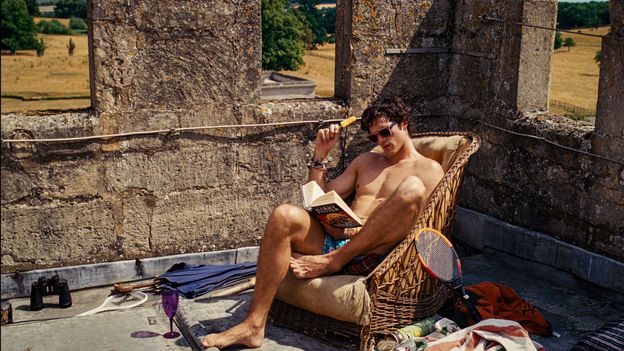

Although it does not offer explicit political critique, Orlando radically centres queer culture, and is full of references that speak to LGBTQI+ viewers across the generations. By casting an 83-year-old Quentin Crisp as Queen Elizabeth I, Potter pays tribute to a gay icon while adding another layer to the film’s discussion of identity. Described by Potter as “the Queen of Queens,” Crisp would go on to identify as transgender and use she/her pronouns in the final years of her life. Rewatching the film with this knowledge adds a dimension to the film’s reflections on the mutability of gender.

Elsewhere, a recurring cameo from musician and activist Jimmy Somerville gestures towards a younger generation. Somerville first appears as a Tudor countertenor in the film’s opening scenes before popping up again across each of the film’s eras. A final surreal appearance at the film’s conclusion – in which Somerville stars as a tinfoil-clad angel singing in the sky – seems to reference the Aids crisis, which at that moment was having a devastating effect on the queer artistic community within which Potter was working.

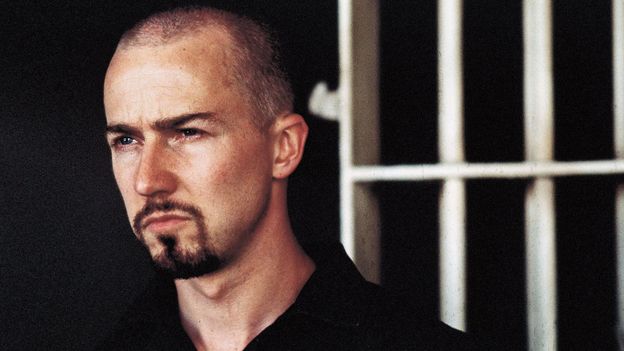

One high-profile victim was Derek Jarman, who would die of Aids-related illnesses in 1994. Although not directly involved in Orlando, Jarman was an important influence. Potter and Jarman had first become friends in the mid-1980s when visiting the then-Soviet Union as part of a delegation of independent filmmakers. “As the only gay male and the only female directors in the group we became natural allies,” Potter remembered. Jarman publicly advocated for Potter as she struggled to get Orlando made, and the film is indebted to Jarman’s iconoclastic approach to period drama, as seen in Caravaggio (1986) and Edward II (1991). Potter also recruited several Jarman collaborators, most notably Swinton, and the costume designer Sandy Powell. In Orlando, Potter draws upon Jarman’s pioneering “queering” of the historical genre, and in doing so furthers a legacy that has been continued in recent subversive period pieces such as The Favourite.

An enduring message

Given these ties to queer culture, it’s unsurprising that Orlando often provokes strong reactions in LGBTQI+ viewers. Mayer has written a book on Potter and is currently working on a monograph about Orlando. They remember vividly the first time that they saw the film as teenagers in 1993. “My friends hated it, and wanted to leave; I was enrapt and wouldn’t,” recalls Mayer. “So my first memory of watching the film is having a furious row in whispers with my then-best friends, who walked off after the screening.” Years later, Mayer realised that part of the film’s appeal was its queerness. “It had given me a window into something that I had only glimpsed through [long-running BBC pop music programme] Top of the Pops… In some ways, I understood that I loved it for the same reasons that my friends hated it, and that they were reasons, both aesthetic and political, that I couldn’t articulate.”