Baltimore, 1962. A chubby teen girl, Tracy Turnblad (Ricki Lake), is desperate to make it on to her favourite local music programme, The Corny Collins Show, where hip teenagers take part in the latest dance crazes – the Mashed Potato, the Twist, and more – to the live accompaniment of artists such as Frankie Avalon and the like. When she gets a guest spot on the show and becomes a teen icon overnight, she starts a fight to bring racial integration to the show.

More like this:

– The greatest comic book movies ever made

– 11 of the best films to watch in June

– David Lynch on ‘the beauty in the dark’

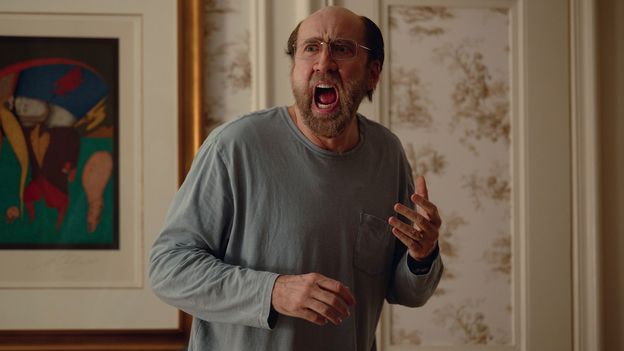

Thirty-five years after the release of John Waters’ Hairspray, it’s fair to say that it’s probably one of his most recognisable and lucrative films. On 9 June, Park Circus re-releases the 1988 film in UK cinemas, and its feel-good rep notwithstanding, it is deeply entwined with Waters’ own upbringing (also in 1960s Baltimore.) In a long career spanning some of the most reviled and controversial of B-movies, wherein crossdressing, eating excrement, and putting infants in fridges was par for the course, Hairspray has long felt like Waters’ most personal film. Given the glittering mainstream treatment of Hairspray in its hit stage musical and in its 2007 remake, which Waters produced, it may seem like an outlier in the career of the so-called “Pope of Trash”, but look closely and you see the subversion is clearly still there. BBC Culture had a chat with the eminent John Waters on the eve of the re-release of his modern classic.

Christina Newland: Do you see Hairspray as any sort of, maybe not a turning point, but a kind of point in your career where there was a shift in terms of budget and audience?

John Waters: Absolutely. I say there are three major turning points in my career. The first was when Pink Flamingos finally played in New York after playing everywhere else in the country. Then it was Hairspray. And the final one was when my book became a New York Times bestseller.

CN: There’s no part of you that is ever annoyed by how mainstream it became?

JW: No! I love it. Divine is a man but Tracy Turnblad doesn’t think her mother is a man. It’s a secret between Divine and the audience, and it’s become totally accepted. And even racists love Hairspray, because they’re stupid and don’t realise I’m making fun of them.

CN: It’s been well documented that the Corny Collins Show is based on a Baltimore show called the Buddy Deane Show, a local version of American Bandstand. But in real life, they didn’t racially integrate. Is there a value in revising history on film for you?

JW: Yes, I gave it a happy ending, and in real life that didn’t happen.