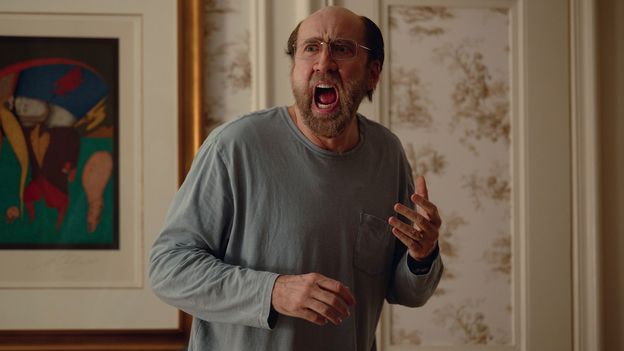

Not that this is the only one of his issues that gets an airing. By the end of the film, Aster has abandoned any pretence of telling a straightforward story, preferring, it seems, to write down all of his darkest, most intimate fears and fantasies about sex, illness, parenthood, money, society and death, and then present them as a kaleidoscopic collage of sitcom, cartoon, crime thriller, monster movie and science-fiction odyssey. The result seems nakedly personal while echoing the comic invention of Woody Allen’s early films, the formal precision of Stanley Kubrick, and the bleak, deadpan surrealism of Roy Andersson, with bits of Charlie Kaufman and David Cronenberg thrown in.

Viewers are sure to be impressed by Aster’s prodigious imagination and technical skill, amused by his gallows humour, and amazed by some of the outrageous images he puts on screen. But whether they will be enthralled by the film is another matter. It’s clear from the start that Beau Is Afraid is set in a heightened alternate reality where our rules don’t apply, and the impression that none of it has any internal logic or tangible consequences can leave you feeling as if somebody is recounting a weird dream they’ve had – and doing so for three long hours. Throughout those three hours, the mewling Phoenix doesn’t convey much more than the abject sadness and self-pity that drip from him in the film’s opening minutes, and the episodic structure means that while each segment is fascinating in its own right, they don’t together contribute anything essential to the narrative. If Aster had simply chopped out the second of the film’s three hours, it might have been more coherent, not less.