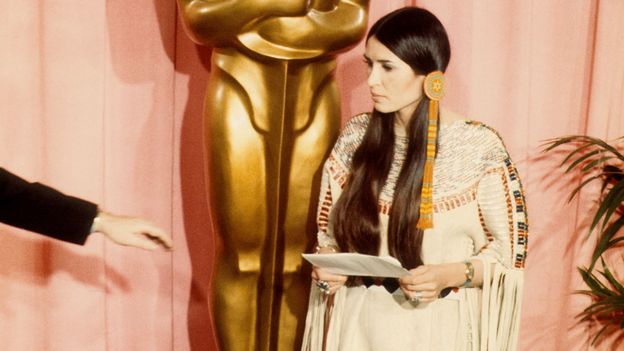

What is true, according to Littlefeather, is that she felt harassed and discriminated against for her speech for most of the rest of her life and career, saying she’d been effectively blacklisted by the entertainment industry. By the end of the 70s, after some small appearances in a handful of movies like Freebie & the Bean and a couple of Playboy spreads, any showbusiness career she might have had seems to have sputtered out. In June last year, the Academy issued Littlefeather a formal apology, and subsequently hosted “an evening of conversation, healing and celebration” with the activist only a month or so before she passed away aged 75 in October. Undoubtedly, the apology was long overdue.

A twist in the tale

Complicating matters further, Littlefeather’s own Yacqui and Apache background has been called into question over the years, most recently in this San Francisco Chronicle piece. If it is to be believed, there are deep-rooted racial and ethical issues attached to Littlefeather and her appearance on stage that evening. If Littlefeather was actually “Pretendian”, as those who falsely claim to be Native American are sometimes called, it may complicate the earnest righteousness of the gesture, and raise questions about how to judge Brando’s choice to use her as his mouthpiece.

However, the facts remain cloudy: the writer of the piece, Jacqueline Keeler, has been challenged on some of her fact-finding by Native American community members, making the identifying of Littlefeather’s heritage a murky proposition.

Adam Piron, the director of the indigenous programme at Sundance Institute, says: “For me, it’s a non-issue to some extent. Whether she was or wasn’t enrolled in the tribes she claimed, she clearly had a lot of acceptance from leaders in our community, who knew about these allegations. The thing that happened with Brando with the Oscars had such an estimable impact in the real world: you’re able to measure what she did in terms of [breaking] the [media] blackout [around Wounded Knee, where the US Justice Department banned journalists], and how that started to change actual policy and legislation around Native Americans because of visibility.”

Considering the text of Brando’s full statement, which Littlefeather was not allowed to read in full on the evening but was later shared with the press, it seems difficult not to see to the heart of the matter:

“It has not been my wish to offend or diminish the importance of those who are participating tonight,” Brando’s full statement said. “Perhaps at this moment, you are saying to yourself, what the hell has this got to do with the Academy Awards? […] the motion picture industry has been as responsible as any for degrading the Indian. When Indian children watch television and they watch films, and they see their race depicted as they are in films, their minds become injured in ways we can never know. If we are not our brother’s keeper, at least let us not be his executioner.”

Fundamentally, questions over Littlefeather’s precise heritage do not lessen the message she delivered – and by extension, Brando’s intention to bring awareness to the plight of Native Americans and to their years of insulting and outright racist representation on-screen.

“I think it’s up to indigenous people to decide how they feel about Littlefeather’s heritage,” says Piron. “But because of her actions and the platform Brando allowed this cause to have, there was a measurable impact. […] It was a part of a larger effort that set the stage for everything that was to follow – increased activism across indigenous communities, much more awareness from non-indigenous communities of what our rights were. And different federal policies around increased recognition of indigenous peoples’ sovereignty from a legal standpoint, whereas before, the idea of US policy was essentially going to be the termination of the identity of the Native American, so he would just be an American.”

Brando – a remarkable actor and a long-time supporter of civil rights, who took part in the 1963 March on Washington – undeniably had his heart in the right place, and in a very modern one, at that, in his invocation of children, cinema, and representation – and as Piron points out, what he and Littlefeather chose to do made a difference that many outside of the indigenous community may not realise. “It kind of flipped the dynamic of the media blackout and the erasure of what was going on. People were looking away, and this sort of forced people to go and look at it.”

It may be that the behaviour of a few hundred attendees of one of the most exclusive and renowned Hollywood events seems like the stuff of superficial celebrity gossip or tabloid fodder. But it’s clear that such Oscars furores often have more to say than first meets the eye.

It stands to reason, given how audiences are used to projecting values and traits onto film stars. So just as the Will Smith/Chris Rock incident sparked a discourse around racial dynamics, showbiz power, beauty standards, and the acceptability of violence, the Brando/Littlefeather incident has become a litmus test around celebrity activism, political divisiveness in the industry, and the real-world efficacy of making statements from such a platform. Over the years, awards controversies like this one have proved a reliable – if often out-of-left-field – bellwether for the most bruising and provocative subjects in our culture and society at large. Let’s hang on tight for Oscars 2023 and see if anything can top it.

Love film and TV? Join BBC Culture Film and TV Club on Facebook, a community for cinephiles all over the world.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.