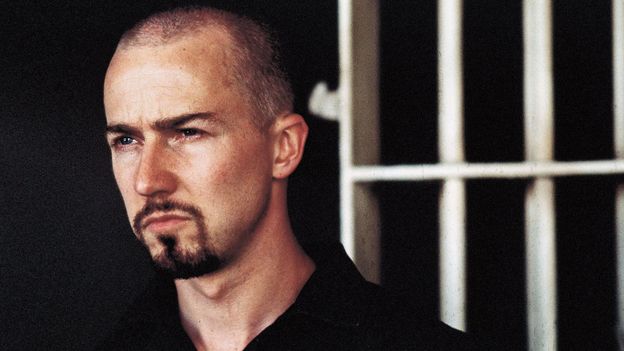

Derek’s crime was an act of intense brutality, portrayed in gut-wrenching detail. In a monochrome flashback, Derek, clad only in white boxers and black military-style boots, his chest emblazoned with a swastika tattoo, shoots two black men in his front garden who’d been trying to steal his car in a turf-war retaliation, killing one instantly. The other, wounded but still conscious, lies sprawled in the grass and Derek proceeds to kill him by stomping his head on the kerb. Soon after, police sirens arrive to bathe Derek in shimmering light, and he raises his hands behind his head in an almost messianic pose of martyrdom. From this pivotal moment, the film traces the circumstances that kindled Derek’s rage and shaped it into racialised grievances, the hollow disillusionment that follows, and his uncertain quest for redemption.

Writer David McKenna drafted the script in six weeks as the 1992 LA Riots, set off by the Rodney King beating, raged outside his apartment. After finishing a second draft, he consulted with Tony Kaye, a British ad director who had been tapped to direct his first feature film. Kaye led McKenna to a skinhead party where the screenwriter took down information from a white nationalist. “For a half hour I talked to a guy with an M-16 tattooed to the side of his head. It was pretty intimidating, if not terrifying,” recalled McKenna. After shooting on the film wrapped, Tony Kaye’s behaviour went from mercurial to outright bizarre. At meetings with New Line Cinema representatives, he brought along a religious retinue of a rabbi, a priest, and a monk in a strange bid to convince executives that his film was not a commercial product but a prophecy.

But a real fight began when Norton inserted himself into the stalled editing process to cut a version of the film that added 18 minutes to its runtime – and played to rave responses from test audiences. In a jealous fury, Kaye dumped $100,000 into paid advertisements in the Hollywood press savaging what he saw as duplicitous meddling by his lead actor. When the studio moved forward with Norton’s cut, Kaye fought to strip his name from the credits, and finally filed a $200m lawsuit against New Line, which was ultimately dismissed. A decade on, Kaye admitted his ego got the best of him: “Whenever I can, I take the opportunity to apologise to all the people that I aggravated. I was doing my best, it was my passion, but I was still completely in the wrong.”

Challenging a persistent myth

A brilliant film emerged from these skirmishes – but its core insight still takes work to unpack. For generations, a persistent myth that black families were irreparably broken by sloth and hedonism had been perpetuated by US culture. Congress’s landmark 1965 Moynihan Report, for example, blamed persistent racial inequality not on stymied economic opportunity but on the “tangle of pathologies” within the black family. Later, politicians circulated stereotypes of checked-out “crackheads” and lazy “welfare queens” to tar black women as incubators of thugs, delinquents, and “superpredators“. American History X made the bold move of shifting the spotlight away from the maligned black family and on to the sphere of the white family, where it illuminated a domestic scene that was a fertile ground for incubating racist ideas.