BBC Culture asked the filmmakers why they had chosen not to consult Taylor on his depiction. They said: “The university’s version of events has been extensively documented over the past 10 years. Philippa’s recollection of events, as corroborated by the filmmakers’ research, is very different.”

And yet Langley’s side of the story has also been “extensively documented”. There’s an award-winning 2013 documentary, Richard III: The King in the Car Park, first shown on Channel 4 and presented by Simon Farnaby. Langley effectively stars in it and was an associate producer. It features Taylor, briefly, and several other university employees. That programme was swiftly followed up with another documentary, Richard III: The Unseen Story, “In this film, those involved tell the full story,” says Farnaby in his introduction. Again, Langley was an associate producer; again, university employees were featured.

And in her book, Langley actually thanks Taylor and the university: “To that remarkable centre of learning, Leicester University, particularly Professor Mark Lansdale, Dr Julian Boon and Dr Turi King for their many kindnesses, and Richard Taylor, Deputy Registrar, for his decision to support the project.”

It is worth nothing that a 2020 study found that 47% of UK archaeologists are women (it was 46% in 2012), but you might not know that from the movie. According to Taylor: “There’s a theme of misogyny that runs through the film. Now the only way the male writers have been able to do that is by writing out – airbrushing out of the university’s project team – at least three of the senior female academics who were involved. Turi King is not mentioned in the film at all. Nor is Lin Foxhall [professor of Greek archaeology and history], nor is Sarah Hainsworth [professor of materials engineering], who both played a key part. That’s not accidental. That’s in order to present the university as being a male-dominated team against a lone woman. So the male writers, in doing that, have excluded the contribution of those female academics and scientists.”

The filmmakers told BBC Culture in response: “None of them were involved in the search for the king’s remains. The search is the subject of our film, not the DNA analysis. Turi King had one conversation with Philippa prior to the excavation and that related to DNA analysis should the remains be discovered, not the search.”

However King says she was brought onto the project by the university in June 2011, over a year before the excavation started, and that she helped with the excavation and there is footage of her doing it. She tells BBC Culture: “I was so down for a couple of days after seeing it [The Lost King] because I used to be so proud of this massive, wonderful project that was an amazing partnership between so many people, all bringing their expertise to the table. That was the joy of it. So to see it being portrayed like this, particularly in how they portray certain members of the team in such a misleading way, was just so sad really.”

British Archaeology magazine carries a lengthy article, currently being offered as a download, mounting a detailed defence of the university’s team and suggesting The Lost King has got some things badly wrong. So has a film about one indefatigable woman’s quest to right historic wrongs ended up perpetrating its own injustices? After all, as the patron of the Richard III Society said, reputation is “fragile”.

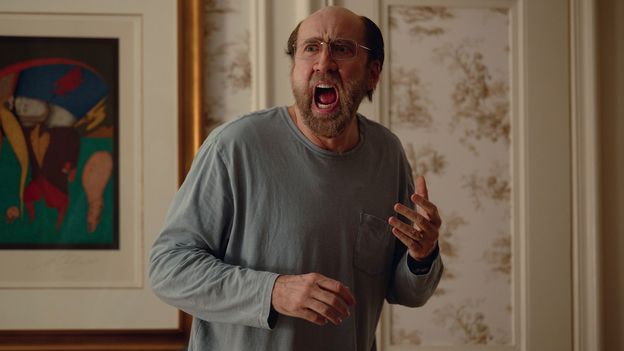

The Lost King is out now in UK cinemas and will be released in the US in 2023.

Love film and TV? Join BBC Culture Film and TV Club on Facebook, a community for cinephiles all over the world.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.