Within Britain, the years immediately following World War Two were marked by austerity, while the Suez crisis of 1956 made it painfully clear that the UK was no longer the political or military superpower it had long prided itself on being. “Britain at that point needed a new story and a new way of understanding itself,” John Higgs, author of Love and Let Die: Bond, The Beatles and the British Psyche, tells BBC Culture. “During the previous couple of centuries, we knew what we were – a global empire. The story we told ourselves was one of Britannia ruling the waves, and the sun never setting on the British Empire. Our sense of identity had gone. We needed a new one. This is where Bond and The Beatles – and the embrace of the modern – came in. They gave us examples of who we wanted to be.”

The sudden fall of the imperial status quo, along with a growing consumer society, set the stage for a radical transformation of British values, spearheaded by popular culture. As working-class, northern English musicians with little formal training, The Beatles defied all preconceived notions of where great art could emerge. Their appearance was startlingly androgynous, their accents undiluted, and their followers adoring. “The band’s unique sound and image suggested to young audiences that success did not mean following a prescribed path,” Christine Feldman-Barrett, author of A Women’s History of the Beatles, tells BBC Culture. “The Beatles demonstrated that trying something new and channelling your talents – no matter your background or who you were – could be a winning combination. That was a powerful message in 1962. It seemed to herald the future. And given the way that young women featured in the band’s early history – including their devout, female fanbase – it was a future that also included women as key players. In this new, vibrant world The Beatles symbolised and implied, everyone mattered, and everyone was welcome to take part in the fun.”

Love Me Do peaked at 17 in the UK charts, the first step in a meteoric rise to unprecedented heights of celebrity. Much of the British establishment had no idea what had hit them. The Conservative politician Ted Heath, then-Lord Privy Seal and future Prime Minister, snobbishly remarked in 1963 that he found it hard to recognise the Beatles’ Liverpudlian accents as “the Queen’s English”. John Lennon shot back, “We’re not gonna vote for Ted”. Two years later, Heath’s party had duly been voted out of office and The Beatles were at Buckingham Palace to collect their MBEs.

Bond and the Beatles’ affinity

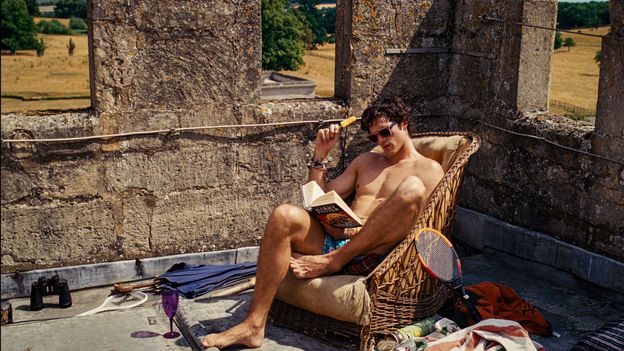

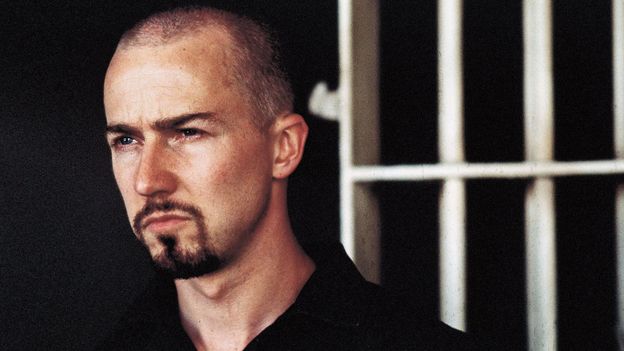

Like The Beatles, the cinematic James Bond established a new model for British life. Ian Fleming’s novels, beginning with 1953’s Casino Royale, had depicted Bond as a broadly reactionary figure. It was the casting of Sean Connery, a working-class actor and former bodybuilder from Edinburgh, that transformed the big screen Bond into a dynamic and modernising hero fit for the sixties. As the producer Albert R “Cubby” Broccoli reflected in his autobiography, “Physically, and in his general persona, he was too much of a rough-cut to be a replica of Fleming’s upper-class agent. This suited us fine, because we were looking to give our 007 a much broader box-office appeal”. The modern action hero was consequently born, combining a classically English sense of style with a tough, transatlantic insouciance, entirely divorced from the effete and aristocratic “gentleman heroes” of earlier British thrillers like Bulldog Drummond. Some cinemagoers were as confused by Connery’s regional accent as Ted Heath had been with The Beatles’. “If you look at the reviews of Dr No, the American reviews, they can’t place his accent, they think he’s Irish,” Llewella Chapman, author of Fashioning James Bond, tells BBC Culture.