Life magazine: The photos that defined the US

(Image credit: International Center of Photography/ Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

Between 1936 and 1972, Life magazine published images that helped to mythologise the US. A new book looks at iconic pictures that shaped how we view a nation, writes Aida Amoako.

W

When Life magazine launched on 23 November 1936, its mission, as stated by its creator Henry Luce, was to enable the American public “to see life; to see the world; to eyewitness great events … to see and be amazed; to see and be instructed…” For the 36 years that marked its golden age, the US weekly informed the country’s views on politics, war, race and national identity through images. With its cohort of star photographers such as Gordon Parks, Margaret Bourke-White and Alfred Eisenstadt, Life helped pioneer US photojournalism. Many of the photographs became iconic works of art in their own right, helping to shape our global collective memory of the 20th Century.

More like this:

– What motherhood is really like

– Can photography save the Amazon?

– A secret history hiding in plain sight

A new book, Life Magazine and the Power of Photography (published by Yale Books with Princeton Art Museum), details how the magazine pioneered the form of the photo essay – and how it both revealed and mythologised the US. When Life first appeared, the US was recovering from the Great Depression and true to its mission, the magazine was determined to show to its mostly middle-class white audience life as millions across the country were experiencing it. Luce (who had launched Time magazine in 1923, and Fortune in 1930) gave as much prominence to images as to words, condensing text into captions for pages of photos.

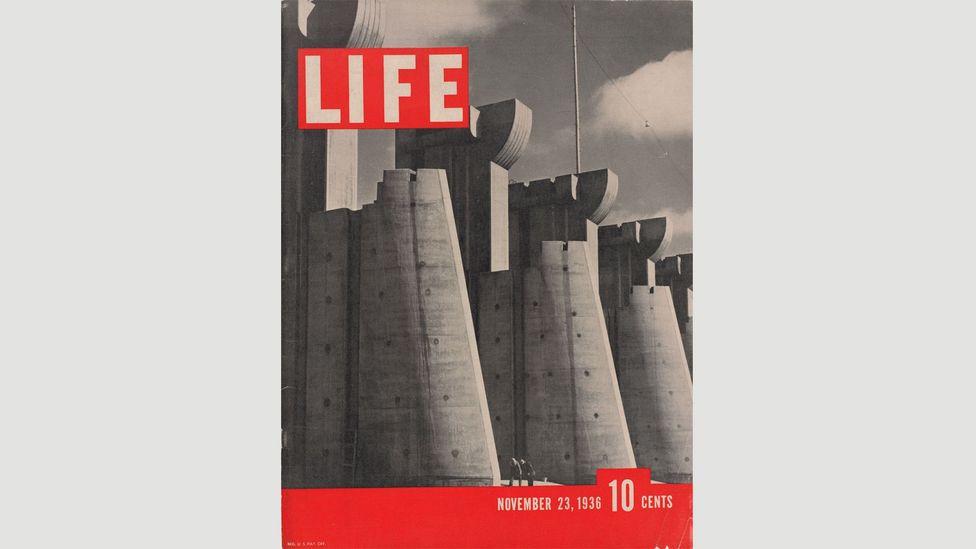

Life’s first cover story was about the construction of the Fort Peck Dam in Montana. Taken by Margaret Bourke-White, the photograph shows the monumental structure, which seems to emit a sense of the ambition of Franklin D Roosevelt’s New Deal, looming over two engineers. Sharon Corwin, chief curator at Colby College Museum of Art, writes in the Life book: “The photograph underscores the tensions between the promises of industrial modernism and the ambiguous status of the American labourer.”

Cover of Life Magazine, 23 November, 1936: photo of Fort Peck Dam by Margaret Bourke-White (Credit: The Picture Collection Inc)

During its run, Life would publish several covers and photos exposing the contradictions in US life. One example is Bourke-White’s 1936 photo of a queue of African-American flood victims waiting for aid beneath a billboard showing a grinning white middle-class family and proclaiming the “highest standard of living”. Another is Thomas D McAvoy’s 1939 photo of African-American singer Marian Anderson performing in front of the Lincoln Memorial, an image that Katherine A Bussard, editor of the Life book and curator of photography at Princeton University Art Museum, suggests was intended to illustrate how the present was “not living up to the nation’s democratic ideals”.

The symbolic significance of the US was of great importance to Luce and Life’s editors and when war broke out in Europe, the magazine took the opportunity to further reiterate its purpose. Luce in particular was in favour of US involvement in World War Two. Months before Pearl Harbour brought the nation into the conflict, he published an editorial titled ‘The American Century’ in which he called on the US to end its isolationism.

When war finally came, Luce commented in Time magazine that “Japanese bombs had finally brought national unity to the United States”. Robert Capa’s photos of the Omaha Beach landings on D-Day (6 June 1944) had a doubly mythic resonance. On the one hand, their blurry quality (caused, according to the published caption, by the “immense excitement”) gave the reader an immersive experience and became part of the visual iconography associated with D-Day. On the other hand, the story that their effect may have been caused by Capa having a panic attack as he faced German shellfire gives an insight into what it meant for Life photographers to be this deeply embedded in the environment of their subjects.

Normandy invasion on D-Day, soldier advancing through surf, 1944 by Robert Capa

Decades later, with the Vietnam War raging, photographers like Larry Burrows would become renowned for their proximity to the theatre of war. Luce, who was loudly pro-US involvement in Vietnam, had stepped down in 1964. While the magazine was struggling with the extent to which it should depict the increasing dissatisfaction with the war, it nevertheless published harrowing photos and seemed to oscillate between humanitarian outrage and imperialistic overture.

Images of a new war

Cemented in US culture by World War Two, Life’s war photography impacted the country’s perception of war overseas. With Allied victory, Life was in a prime position to help shape America’s post-war image and the magazine’s take was more complicated than is perhaps remembered. The magazine’s images of the end of the war, such as the mushroom clouds of the atomic bombs that destroyed Hiroshima and Nagasaki and Alfred Eisenstaedt’s now iconic VJ Day kiss, signalled the complex visual culture of the Cold War that would now ensue. In Eisenstaedt’s photo, an American GI kisses a female stranger in the middle of Times Square during a parade. The shot evokes the sense of unbridled celebration, its composition reminiscent of romantic moments in Hollywood films (despite the more complicated context of the photo).

Detail of contact sheet, Times Square, New York City, August 1945 by Alfred Eisenstaedt (Credit: The Picture Collection Inc)

Professors Robert Hariman and John Louis Lucaites write in an essay in the Life book: “Iconic photographs are those that are widely recognised and remembered, are thought to represent historically significant events, evoke strong emotional identification or response, and are appropriated across a broad range of media, genres and topics.” This photo came to encapsulate the end of the war for many Americans for decades. Yet even before it would attain this legacy, it was clear that Life – as an extremely popular magazine aiming to inspire and instruct – felt the weight of the unchartered territory into which the world had entered: one in which the threat of nuclear war loomed. Life had the reach to influence the new ideological war.

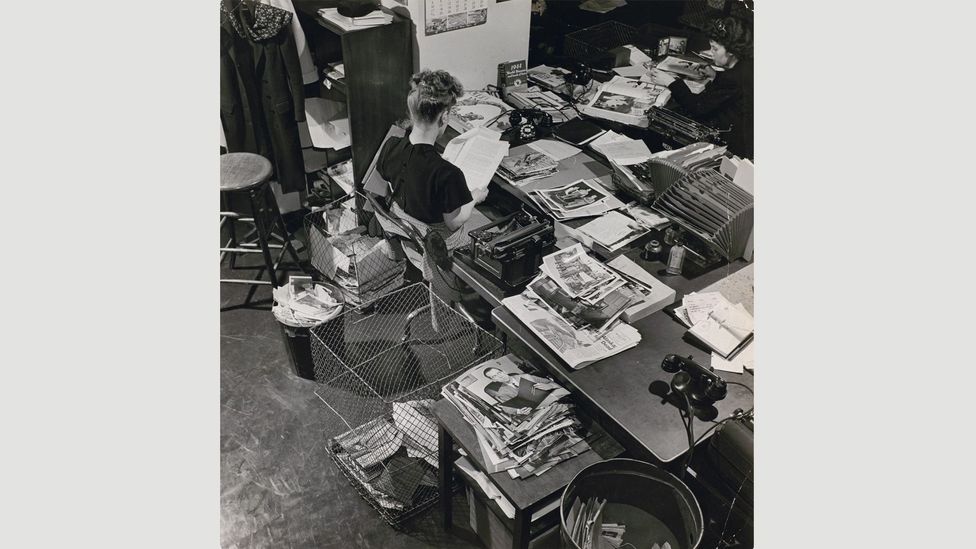

The war had doubled the magazine’s photography staff and while the quality of Life’s photography and paper gave it the feel of monthly magazines, its production rate was closer to that of newspapers. An unknown photographer captured Life photo editor Natalie Kosek reviewing images, the chaotic surroundings giving a sense of the amount of work and the pressure that went into producing the weekly magazine. By 1942, they were sifting through 20,000 images a week.

Life photo editor Natalie Kosek reviews photographs, 1946 by unknown photographer (Credit: The Picture Collection Inc)

Life was at its height in this post-war era which saw the US emerge as an even stronger economic and cultural superpower. The magazine acted as the nation’s mirror, reflecting both myth and reality with photos like Andreas Feininger’s of Route 66 (the 2400-mile – 3800km – road stretching from Chicago to Los Angeles via the arid Mojave desert), which depicts the open road and sky, and evokes the uniquely American myth of the frontier.

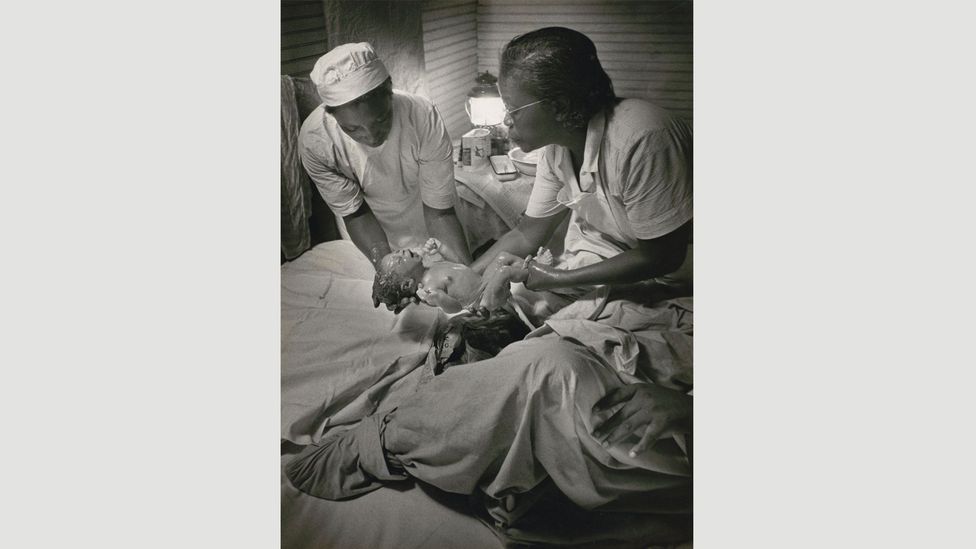

But Life did not shy away from depicting the struggles of rural communities. In 1951, W Eugene Smith followed Maude Callen, a midwife, nurse and community worker who attended to a predominantly black community in Pineville, South Carolina. The star image of the photo essay showed a serenely focused Callen ready to receive a newborn, an image that, for Dalia Habib Linssen at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, “generates a palpable sense of intimacy”. Indeed the response the story received attested to this. Letters poured in, along with donations and food. One subscriber wrote: “In all the years I have been reading Life, I have never been so moved or affected by anything as by your article on Maude Callen.” Callen used the $20,000 raised to open the Maude Callen clinic, where she worked until her retirement in 1971.

Midwife Maude Callen delivers a baby, Pineville, South Carolina, 1951 by W Eugene Smith (Credit: The Picture Collection Inc)

Other photo essays Life published over the years that highlighted overlooked communities would evoke similar responses – most notoriously, perhaps, Gordon Parks’s project telling the story of Flávio da Silva, a 12-year-old boy living in a Brazilian favela. Published 10 years after Smith’s, it invoked an outpouring of empathy, guilt and donations. It also sparked a mini photojournalistic Cold War, with a Brazilian publication sending photographers to document New York’s poor in retaliation against a US ‘saviour’ narrative.

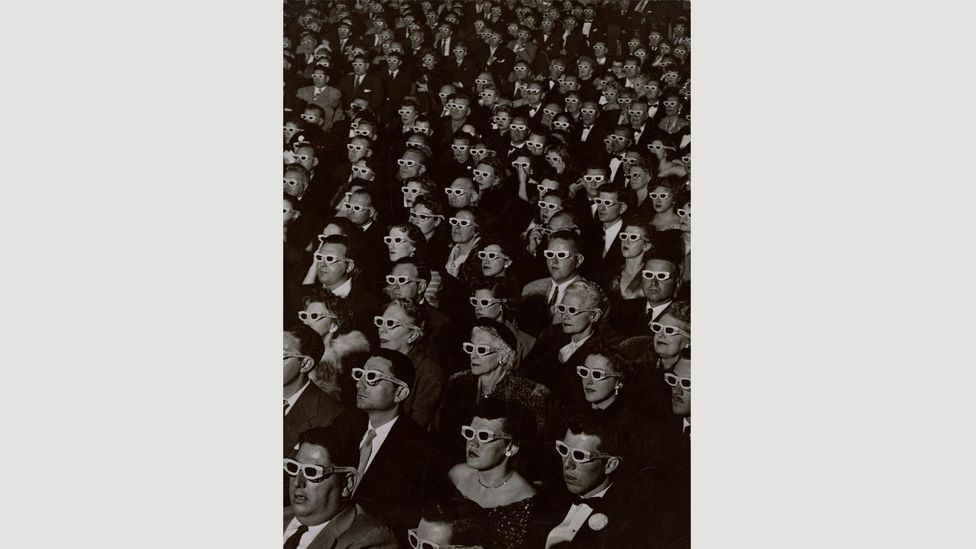

Alongside its depiction of small-town life, the magazine revelled in the stories provided by the world of entertainment. There was the glamour of Hollywood embodied in photos of figures like Steve McQueen and Marilyn Monroe; but Life also followed what rapid developments in film-making meant for audiences. In 1952, J R Eyerman photographed the audience of Bwana Devil, the first full-length colour 3-D movie. With their eyes obscured by Polaroid 3D glasses, it looks like the cinemagoers are transfixed, but apparently they weren’t too impressed.

Audience watches movie wearing 3-D spectacles, 1952 by JR Eyerman (Credit: The Picture Collection Inc/ Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, The Howard Greenberg Collection)

Life reported the ‘megalopic’ audience felt the glasses were uncomfortable and the feature, based on a true story about man-eating lions in Africa, was ‘dull’. But the photo itself transcended the specific occasion it showed. As Princeton University’s Caitlin E Ryan writes in the book, it “reflects the central role that popular entertainment, and Hollywood in particular, played in constructing the magazine’s cohesive vision of American identity at mid-century”. It is no surprise, perhaps, that a section of the photograph became the cover of a 1983 edition of Guy Debord’s The Society of the Spectacle.

Defining the 60s

The 1960s presented a multitude of political and cultural moments for Life to interpret. In 1961, President Kennedy announced part of his Cold War strategy and the magazine responded to the call, expressing the view in June of the same year that it felt the goals of the US were ‘to win the Cold War’ and ‘create a better America’.

Two years later, Kennedy was assassinated. Life had had a close relationship with the Kennedys, documenting John and Jackie’s courtship and wedding as well as the presidency. Life also published Theodore H White’s famous interview with Jackie, the interview in which the Kennedy myth of Camelot was born (and which the magazine would help sustain with its many commemorative pieces and books over the years).

In 1968 things seemed to reach a fever pitch. There was growing anger with the war in Vietnam. Martin Luther King Jr had been assassinated in April and protests broke out across the US. Election campaigning was underway when JFK’s younger brother and 1968 presidential hopeful Robert F Kennedy was assassinated in the kitchen of a hotel. Photographer Bill Epperidge, who had been following Kennedy’s campaign, captured the busboy Juan Romero cradling the Senator. In October at the Summer Olympics in Mexico City, black athletes Tommie Smith and John Carlos raised their fists in protest. John Dominis snapped the photo for Life that showed Smith and Carlos standing, heads bowed, gloved fists in the air, against the jet black of the sky.

As the decade came to a close, the magazine was struggling. Professor of American Studies at University College Dublin, Liam Kennedy, writes in the Life book: “an increasingly divided public no longer saw itself reflected in the pages of Life, and the magazine could not visually suture the divisions in the American worldview”. It could also no longer compete with television news, which had been drawing advertisers away since the beginning of the decade, boosted by its use by presidential candidates. In December 1972, Life published its last weekly issue, which significantly did not have a photographic front cover.

The magazine has continued in various forms, being revived on first a monthly and then a weekly basis as well as published as special reports. Yet despite no longer existing as it once did, Life has maintained a legacy as one of the most important publications in US history. During its run, the magazine published 200,000 pages of photo essays; but specific photographs have come to be considered iconic pieces of work for their cultural, historical and artistic importance. Exhibitions, such as the one currently on display at Princeton University Art Museum, documentaries and archival partnerships with Google and Getty have helped canonise these works – and Time Inc itself continues to burnish Life’s mythology and legacy as America’s mirror through anniversary journalism. To this day, Life’s images force us to ask how photographs both influence and preserve social memory.

Life magazine and the Power of Photography is at Princeton University Art Museum until 21 June 2020, and continues at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, from 19 August to 13 December 2020. A book of the same name has just been published by Yale University Press.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, WorkLife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.